I will be adding notes to this page as we read this book together through our monthly meetings. You should be able to find the link to this page at the top of my blog.

July 15, 2025

July 17, 2025

During our first session we reviewed some of the following from the reading:

Introduction

Most of us could talk for some time about what “spirituality” means to us, or might mean within the larger conversation of our culture. It arose in use in the 17th Century to describe a personal relationship with God with implications of holiness. However, it remains relative subjective in terms of how it is used.

In our contemporary context, “spirituality” might mean any number of things and be attributed to any number of experiences. A consistent and defensible use of the word spirituality is associated with religious/theological themes, and in our case how such themes are centered upon the Christian life. In the early Church it was assumed that anyone writing theology, giving sermons, or offering reflection on the Scriptures would have been doing so as the result of a personal commitment to Christ.

July 17, 2025

During our first session we reviewed some of the following from the reading. I am relying heavily on the work of Richard Schmidt from the book in the following notes.

Introduction

Most of us could talk for some time about what “spirituality” means to us, or might mean within the larger conversation of our culture. It arose in use in the 17th Century to describe a personal relationship with God with implications of holiness. However, it remains relative subjective in terms of how it is used.

In our contemporary context, “spirituality” might mean any number of things and be attributed to any number of experiences. A consistent and defensible use of the word spirituality is associated with religious/theological themes, and in our case how such themes are centered upon the Christian life. In the early Church it was assumed that anyone writing theology, giving sermons, or offering reflection on the Scriptures would have been doing so as the result of a personal commitment to Christ.

“For centuries most theologians were cloistered monks . . . since it addressed the most important thing in human life, humanity’s relationship to God, theology was known as the queen of the sciences, and it was the spiritual dimension of theology that justified the title.”

A precursor to the “modern” era in Europe was the rise of universities, and theology made its way from the monk’s cell and prayer stall to the classroom. Once theological reflection and writing entered the academic arena as subject among subjects, a science among sciences, essentially cordoned off from a life of prayer, the general population began to see it more and more as a specialized subject for a smaller group of students, rather than a general application beneficial to humanity as a whole.

Through the centuries “spirituality” has more and more come to represent and individualized {potentially} experience of transcendence that may occur with our without a particularized relationship with Christ.

Our author makes the point that Christian spirituality will have a particular “flavor” and substance that allows, or compels, us to hold it separately from other religions; and that at some point the old trope “all roads lead to Chicago,” or that all religious roads lead to God, is not actually the case. While we might learn from other paths, there is a particularity in Christianity that will invite an immovable uniqueness – which might also be said of other religious paths.

Spirituality is build upon the foundation of theological belief and religious practice; and for it to be edifying, rather than self-indulgent and disoriented, spirituality is best explored as rooted, or an attachment, to a larger source of meaning.

Christian Spirituality

Spirituality derives from the Latin – spiritus

Spiritus in the Greek – pneuma – moving air

Pneuma in the Hebrew – ruach – wind, breath

Essentially what we are describing is a movement, a power, an experience, an energy that is “unseen.” In the Christian faith there is some room and description given to those who experience God as a mystery. “Rudolf Offo, in his 1917 classic, The Idea of the Holy, calls this the numinous and adds to energy and mystery a third quality: fascination. There is much of this in the Bible. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, then {this is true of some other traditions as well}, spirituality refers to the search for {and to being sought by} what is all-powerful, beyond understanding, and utterly alluring. This is what I referred to as the search for what is important, valuable, and beautiful. The usual name for this is God.”

Put simply, we are looking for such things through a relationship with Christ. Other paths have much to contribute – Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, Aboriginal – but we will be traveling with those who have sought Jesus as the Christ of God.

Polarities to Look For

Holistic verses Dualistic. “The ancient Hebrews saw the material world, including the human body, as God’s creation and a manifestation of God’s glory.” Essentially the Hebrews did not believe that anything spiritual can actually be dislocated from something material. We sometimes thing of the human being as an expression of the “imago dei,” the image and likeness of God; our Hebrew forebearers might say that is true of all that we can see, taste, smell, and touch. The entire created “project” is an extension of God’s presence in our midst. The thinking Greeks – Plato, Aristotle, and the like – often found a gentle separation between the experience of thought and feeling in opposition to living in a material frame. “The Greeks . . . were suspicious of material things and sought to overcome or rise above them, with the human body in particular needing discipline and constraint.”

Christianity is sourced in both of these cosmic assumptions; both to its benefit and detriment. The interplay between a Holistic verses Dualistic interpretation of spiritual or transcendent experiences of God will color the writers we read together.

Mystical versus Cognitive

Some intellectuals, scholars, and writers have an allergic reaction to the entire notion of mysticism. “It suggests something esoteric, superstitious, and occult . . . referring to visions, dreams, and the like – direct, inner experiences of the supernatural, neither mediated nor validated by any doctrine, sacred text, or human influence.”

There have always been these “outliers” in the Church, and sometimes they have paid dearly for their mystical encounters at the hands of those who render and demand that all things of God orbit in the cognitive disciplines. “While most Christian mystics are orthodox in their beliefs, their souls are energized by their direct experiences of the holy.”

Communal verses Individualistic

There has long been tension between the individual and the collective within Christianity. “This reflected the biblical understanding of the holy people or nation and later, of the Church as the body of Christ . . . individual behaviors and beliefs were not overlooked or discounted, but they mattered less than taking one’s place in the community.”

With the rise of learning, individual experience, the value of the individual in the politics and social fabric of the West, there is a corresponding appreciation of individuality in spirituality; or we might even say a “preference” for the individual experience over that of the collective.

Inward versus Outward

For many the spiritual journey is necessarily an inward trajectory that is cultivated through “solitude, prayer, meditation, and acts of self-denial.” However there is also a trajectory that leads outward in a life of service – feeding the hungry, caring for orphans, working for peace and reconciliation, etc. Generally we do not live in one arena well without having a foot in the other.

Prophetic versus Institutional

I might partner this dualism with the notion of individual and the collective; generally, a prophet is a one who has come with a message for the many. Institutional maintenance is sometimes threatened by the solitariness of the individual – especially if that individual is motivated by an experience that either lies hidden, outside, or transcends the responsibilities of the institution in preserving the collective. An illuminated reform is often what the individual brings for the collective; while the collective offers the promise of security and identity to the one living as a solitary.

Spirituality and People

Schmidt points out that this is not a project of simply accumulating ideas – it is a project of getting to know people who happened to be having the significant ideas. “God lives in the hearts of flesh-and-blood human beings, not in mental constructs, inspirational thoughts, and sublime truths.” These “spiritualities” are particularized in the lives of actual people who walked through the world bearing the institutional, denominational, historical, and social limitations that we each share. Some of them have much in common, some little; the unifying thread through their lives is that sought a deeper communion with Christ, or were inexplicably called into that union by divine appointment.

“One other thing emerges from these biographies – virtually all the people discussed in this book changed as they grew older, and in more than the inevitable ways that come with aging . . . some of them ended their lives in a radically different place from where they had begun.”

This is what comes of being willing to give our lives to the larger things and the larger questions of human existence – we do not get to remain immobile.

Irenaeus

Irenaeus planted the flag of an infant Christian orthodoxy into the extremely heterodox world of the ancient Roman and Greek Western culture. Schmidt does a good job of summarizing the competing cosmic and human allegiances that early Christians and seekers faced as they sought to make sense of the notion that “God became human so that humans might become God.” Irenaeus was wrestling with those Gnostics who wanted to make the case that Jesus came with a secretive or esoteric “gnosis,” knowledge, of which only a few might partake. All we have to do is look at our penchant for secret societies – Masonic lodges, initiation rites of various fraternities and sororities, and other “top secret” societies – in order to see where such motivations are born.

The incarnation of Jesus as the Christ of God is the central message of Irenaeus. He also believed that the local “episcopos,” Bishop, was the individual responsible for seeing that the teaching of the Gospel, and the message of salvation offered to all, remain unentangled with philosophical and theological disputes which might compromise the message of God’s love for all humanity. The Bishops of the early Church were the inheritors of the first apostle’s contact and instruction from Christ.

“To understand Irenaeus, we must recognize that modern Westerners, especially Americans, think in terms of the individual, whereas the ancients took a more corporate view of humanity.”

“The key player in this cosmic process {recapitulation of humanity in Christ} was the divine logos, usually translated – Word. The idea of the logos derives from the Jewish notion of a pre-existing Messiah and was taken up by Philo, an Alexandrian Jewish philosopher who lived at the time of Christ. Philo saw the logos as the preexistent mind or reason, the creative power that fashions the world, and the intermediary between God and humanity.”

Thoughts and Asides about Irenaeus:

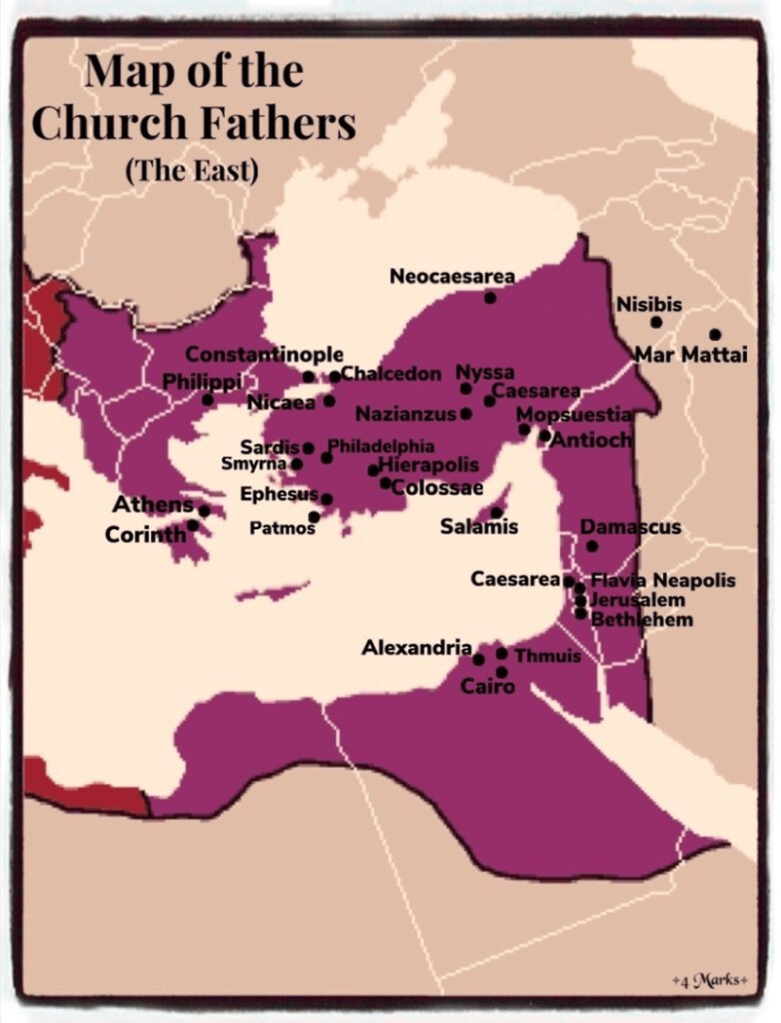

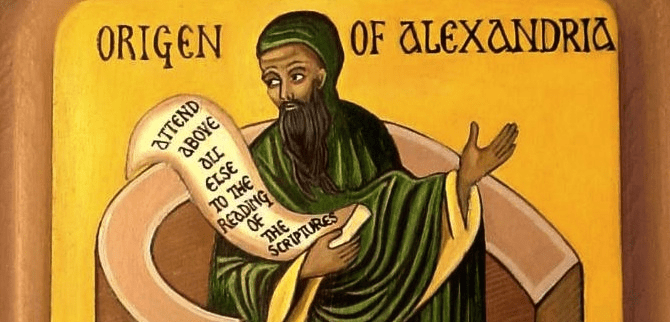

ORIGEN OF ALEXANDRIA – 185 to 254 AD

I have been reding Origen since discovering him in seminary, where I stumbled into the “Bridal Mysticism” that is associated with the exegesis of the Song of Solomon – The Song of Songs. Origen’s work on the The Song as a template for the union that is longed for between the individual soul and God is the foundational work for many subsequent commentators and spiritual seekers. Richard Schmidt points out that no churches, schools, streets, or cities are named for Origen because he never made the “A team” of the patristics. This is probably because he was heavily influenced by the neo-Platonists of his day, as well as undertaking mid-life castration as a physical sign of his surrender to the spiritual life; Origen liked to find God on the edges of consciousness and experience.

Origen was born very much an “insider” within the early Church, with a father who was eventually martyred for his faith. As a teen, Origen encouraged his father to remain firm in his faith, and over the course of his own life Origen would see martyrdom, self-offering, as the highest and chief calling of any follower of Jesus. Origen became a famous teacher and preacher in Alexandria, and eventually joined that circuit of ancient rhetoricians and speakers who toured the larger cities of the ancient world – he was a person of note within his own day. He eventually ended up in the Holy Land – living in Caesarea – where he studied, wrote, preached, and was ordained to the priesthood.

With the rise of Emperor Decius and the extreme persecution of Christians, Origen was imprisoned and treated roughly by the Roman authorities; this would eventually shorten his life, and he ended his days with a broken body. It may have been his persecution which added to the weight of his teaching amid early Christians. This was a very fluid time within the teaching and doctrine of the Church, and there were any number of theological and philosophical permutations making their way into Christian hearts and minds. As a Platonist, Origen tended toward the universal in his thinking; the carpenter, the man Jesus, the individual was an historical fact, however Origen found in Jesus the launch pad into cosmic and eternal considerations about the nature of the universe and life as a whole.

Jesus was both in time, as well as beyond time; a figure who cast a shadow within this frame of time and space as a mortal, but simultaneously a figure who could step through that fabric as no other human being know to mankind. Origen used the theological and philosophical ingredients associated with the divine Logos in his exploration and description of the significance that Jesus, born in Bethlehem, raised in Nazareth, was and is the only Son of God.

Jesus, The Son, The Logos, is the “spotless mirror” of the deity we call God the Father.

“The Father’s begetting of The Son is a continuous act of the divine will. It was this cosmic Christ who assumed bodily form in the person of Jesus.” {Schmidt 14}

https://www.modernreformation.org/resources/articles/origen-of-alexandria-to-be-and-to-be-called-a-christian {wonderful article by Blake Adams at “Modern Reformation”

Comprehensive Background:

Summary of Biography of Origen:

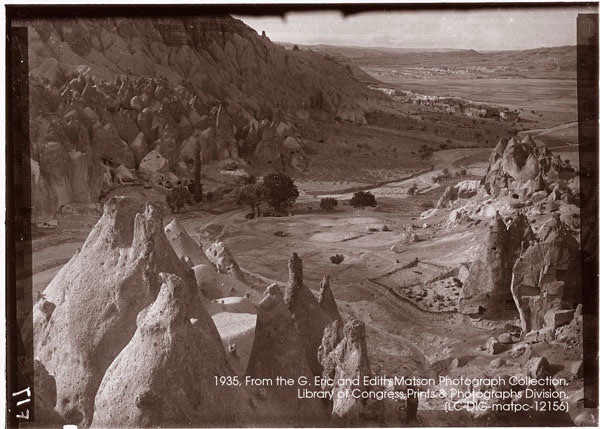

ANTHONY OF EGYPT {251-355}

Our venerable and God-bearing Father Saint Anthony the Great was born into a wealthy family in upper Egypt about 254 AD. Also known as Anthony of Egypt, Anthony of the Desert, and Anthony the Anchorite, he was a leader among the Desert Fathers, who were Christian monks in the Egyptian desert in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. The Orthodox Church celebrates his feast on January 17.

Life of St. Anthony

Most of what we know about the life of St Anthony is in the Greek vita (Life of Antony) by Athanasius, circulated in Latin. Several surviving homilies and epistles of varying authenticity provide scant autobiographical detail.

Anthony was born near Herakleopolis Magna in Upper Egypt in 251 to wealthy parents. When he was eighteen years old, his parents died and left him with the care of his unmarried sister. In 285, he decided to follow the words of Jesus who had said: “If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasures in heaven; and come, follow Me.” (Matthew 19:21). Anthony gave his wealth to the poor and needy, and placed his sister with a group of Christian virgins, a sort of proto-nunnery at the time.

The moniker “Father of Monasticism” is misleading, as Christian monasticism was already being practiced in the deserts of Egypt. Ascetics commonly retired to isolated locations on the outskirts of cities. Anthony is notable for being one of the first ascetics to attempt living in the desert proper, completely cut off from civilization. His anchoritic (isolated) lifestyle was remarkably harsher than his predecessors. By the 2nd century there were also famous Christian ascetics, such as Saint Thecla. Saint Anthony decided to follow this tradition and headed out into the alkaline desert region called the Nitra in Latin (Wadi El Natrun today), about 95 km west of Alexandria, some of the most rugged terrain of the Western Desert.

Also note that pagan ascetic hermits and loosely organized cenobitic communities that the Hellenized Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria described as the Therapeutae in the first century, were long established in the harsh environments by the Lake Mareotis close to Alexandria, and in other less-accessible regions. Philo understood: for “this class of persons may be met with in many places, for both Greece and barbarian countries want to enjoy whatever is perfectly good.” (Philo, De vita contemplativa, written c. 10)

According to Athanasius, the devil fought St Anthony by afflicting him with boredom, laziness, and the phantoms of women, which he overcame by the power of prayer, providing a theme for Christian art. After that, he moved to a tomb, where he resided and closed the door on himself, depending on some local villagers who brought him food. When the devil perceived his ascetic life and his intense worship, he was envious and beat him mercilessly, leaving him unconscious. When his friends from the local village came to visit him and found him in this condition, they carried him to a church.

After he recovered, he made a second effort and went back to the desert, further out, to a mountain by the Nile, called Pispir, now Der el Memun, opposite Arsinoë in the Fayyum. There he lived strictly enclosed in an old abandoned Roman fort for some twenty years. According to Athanasius, the devil again resumed his war against Saint Anthony, only this time the phantoms were in the form of wild beasts, wolves, lions, snakes and scorpions. They appeared as if they were about to attack him or cut him into pieces. But the Saint would laugh at them scornfully and say, “If any of you have any authority over me, only one would have been sufficient to fight me.” At his saying this, they disappeared as though in smoke, and God gave him the victory over the devil. While in the fort he only communicated with the outside world by a crevice through which food would be passed and he would say a few words. Saint Anthony would prepare a quantity of bread that would sustain him for six months. He did not allow anyone to enter his cell: whoever came to him, stood outside and listened to his advice.

Then one day he emerged from the fort with the help of villagers to break down the door. By this time most had expected him to have wasted away, or gone insane in his solitary confinement, but he emerged healthy, serene, and enlightened. Everyone was amazed he had been through these trials and emerged spiritually rejuvenated. He was hailed as a hero and from this time forth the legend of Anthony began to spread and grow.

Then he went to the Fayyum and confirmed the brethren there in the Christian faith, then returned to his old Roman fort. Anthony wished to become a martyr and went to Alexandria. He visited those who were imprisoned for the sake of Christ and comforted them. When the Governor saw that he was confessing his Christianity publicly, not caring what might happen to him, he ordered him not to show up in the city. However, the Saint did not heed his threats. He faced him and argued with him in order that he might arouse his anger so that he might be tortured and martyred, but it did not happen.

When he went back to the old Roman fort, many came to visit him and to hear his teachings. He saw that these visits kept him away from his worship. As a result, he went further into the Eastern Desert of Egypt. He travelled to the inner wilderness for three days, until he found a spring of water and some palm trees, and then he chose to settle there. On this spot now stands the monastery of Saint Anthony the Great. On occasions, he would go to the monastery on the outskirts of the desert by the Nile to visit the brethren, then return to his inner monastery.

The backstory of one of the surviving epistles, directed to Constantine I recounts how the fame of Saint Anthony spread abroad and reached Emperor Constantine. The Emperor wrote to him, offering him praise and asked him to pray for him. The brethren were pleased with the Emperor’s letter, but Anthony did not pay any attention to it, and he said to them, “The books of God, the King of Kings and the Lord of Lords, commands us every day, but we do not heed what they tell us, and we turn our backs on them.” Under the persistence of the brethren who told him, “Emperor Constantine loves the church,” he accepted to write him a letter blessing him, and praying for the peace and safety of the empire and the church.

According to Athanasius, Saint Anthony heard a voice telling him, “Go out and see.” He went out and saw an angel who wore a girdle with a cross, one resembling the holy Eskiem (Tonsure or Schema), and on his head was a head cover (Kolansowa). He was sitting while braiding palm leaves, then he stood up to pray, and again he sat to weave. A voice came to him saying, “Anthony, do this and you will rest.” Henceforth, he started to wear this tunic that he saw, and began to weave palm leaves, and never got bored again. Saint Anthony prophesied about the persecution that was about to happen to the church and the control of the heretics over it, the church victory and its return to its formal glory, and the end of the age. When Saint Macarius visited Saint Anthony, Saint Anthony clothed him with the monk’s garb, and foretold him what would be of him. When the day drew near of the departure of Saint Paul the First Hermit in the desert, Saint Anthony went to him and buried him, after clothing him in a tunic which was a present from St Athanasius the Apostolic, the 20th Patriarch of Alexandria.

When Saint Anthony felt that the day of his departure had approached, he commanded his disciples to give his staff to Saint Macarius, and to give one sheepskin cloak to Saint Athanasius and the other sheepskin cloak to Saint Serapion, his disciple. He further instructed his disciples to bury his body in an unmarked, secret grave, lest his body become an object of veneration. He stretched himself on the ground and gave up his spirit. Saint Anthony the Great lived for 105 years and departed on the year 356. He probably spoke only his native language, Coptic, but his sayings were spread in a Greek translation. He himself left no writings. His biography was written by Saint Athanasius and titled Life of Saint Anthony the Great. Many stories are also told about him in various collections of sayings of the Desert Fathers.

Some of the stories included in Saint Anthony’s biography are perpetuated now mostly in paintings, where they give an opportunity for artists to depict their more lurid or bizarre fantasies. Many pictorial artists, from Hieronymus Bosch to Salvador Dalí, have depicted these incidents from the life of Anthony; in prose, the tale was retold and embellished by Gustave Flaubert.

Founder of monasticism

Saint Anthony and Saint Paul the Hermit are seen as the founders of Christian monasticism. Saint Paul the Hermit is lauded by Saint Anthony as the first hermit. The monastery of Saint Paul the Hermit exists to this day in Egypt. Saint Anthony himself provided the example that others would follow (see Saint Pachomius). Anthony himself did not organize or create a monastery, but a community grew up around him based on his example of living an ascetic and isolated life. Those who wished to follow him needed the company of others to survive the harsh conditions.

https://www.saintsophiadc.org/life-saint-anthony-great-anchorite-egypt-father-monks/ {Saint Sophia Greek Orthodox Cathedral 2815 36th Street, NW Washington, D.C.}

SAINT ANTHONY, THE FIRST DESERT FATHER

https://youtu.be/M2SA-8gQ7aw?feature=shared

GREGORY OF NYSSA {335~395}

https://stgregs.info/parish-life/patron-saint-gregory-of-nyssa/

St. Gregory of Nyssa,

Our Father of Fathers

by Victor M. Rentel

St. Gregory of Nyssa was one of a group of illustrious 4th Century saints who left an enduring imprint on the Orthodox Church.

With St. Basil, the Great, St. John Chrysostom, and St. Gregory, the Theologian, St. Gregory of Nyssa created a rich legacy of theology, liturgy, and spiritual literature unsurpassed in any era of the Eastern Church. This body of work is vastly important for its interpretation of Eastern Christianity’s theology, liturgical texture, and the nature of God. Orthodoxy’s distinctive mysticism has its origins in this period with much owing to St. Gregory of Nyssa.

Like other saints, St. Gregory of Nyssa was a unique and gifted human being with extraordinary powers of observation and expression. His family was equally remarkable, an intellectual and spiritual citadel in the Church’s history. St. Gregory’s brother, St. Basil, the Great, not only wrote one of the core liturgies of the Orthodox Church, he created prayers that today remain commonplace in the lives of ordinary Orthodox believers, and he educated or served as an icon for clergy and bishops of his and later ages. Basil, with his brother Gregory, helped to establish our understanding of the Trinity and of the distinctive nature of Christ within the Trinity. Their saintly mother, Emmelia and renowned lawyer father raised nine children–five girls and four boys—of whom, one brother Nacratious was a lawyer and another, Peter was the Bishop of Sebasta, a small town on the Mediterranean coast.

If the other brother and four sisters, little is known. Macrina, Gregory’s older sister, was widely known and beloved for her devout and holy life, who ultimately was honored as a saint. She was Gregory’s confidant, sometimes intellectual partner, and deep spiritual influence, who probably influenced his ordination decision. St. Basil, in all likelihood, was the driving force in St. Gregory’s decision to pursue holy orders. St. Basil appears to have been the dominating intellectual and social force in Gregory’s life and probably in Peter’s life as well. In a letter to Peter, St. Gregory expressed his deep gratitude to their older brother Basil whom Gregory described as “our father and our master.” The letter conveyed great affection for Basil and for Peter as well.

Most scholars agree that St. Basil played a principal role not only in guiding Peter’s and Gregory’s life choices but equally in educating and raising his younger brothers.

St. Gregory was a reluctant cleric. He had trained for and started a career as a teacher of rhetoric, the study of effective pubic speaking and writing. His family, however, did not support his career choice and tried to convince Gregory to use his talents in the service of the Church. When he chose to become a teacher, his brother Basil, by then a powerful bishop, objected to and argued against St. Gregory’s choice with long and impatient letters to his younger brother. St. Basil initially failed to persuade his young brother of his mistake, but ultimately with Gregory’s friends and sister, Macrina, St. Basil persuaded Gregory to become a priest. Shortly thereafter, Gregory was elevated to Bishop of Nyssa.

St. Gregory’s large body of theological work and his many letters constitute an eloquent and intellectually distinctive contribution to Orthodox theology and spirituality. His Catechism is testimony to his profound grasp of Christian belief. In The Life of Moses, St. Gregory’s mystical portrayal of God–simultaneously audacious and humble and thoroughly brilliant—has no parallel in Christian thought. Similarly, his letters are models of elegant grace and beauty, some miraculously anticipating a style of writing and thought not to arise until 1400 years later in the Romantic era of western literature. He was a gifted writer and speaker who delighted in language and its power to persuade and invoke the senses while illuminating the intellect, a wholly unmatched attribute among writers of his period and unique among the early Church Fathers.

In 787 A.D., roughly four centuries after Gregory’s death, the Seventh General Council of the Church honored St. Gregory of Nyssa by naming him, “Father of Fathers.

St. Gregory of Nyssa, whose mystical rejoicing of the Trinity and consuming love for his fellow human beings, continues to touch our souls as, Father Gregory, the sublime catechist, reluctant cleric, and unlikely hero of the Church.

https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2011/01/saint-gregory-of-nyssa-father-of.html

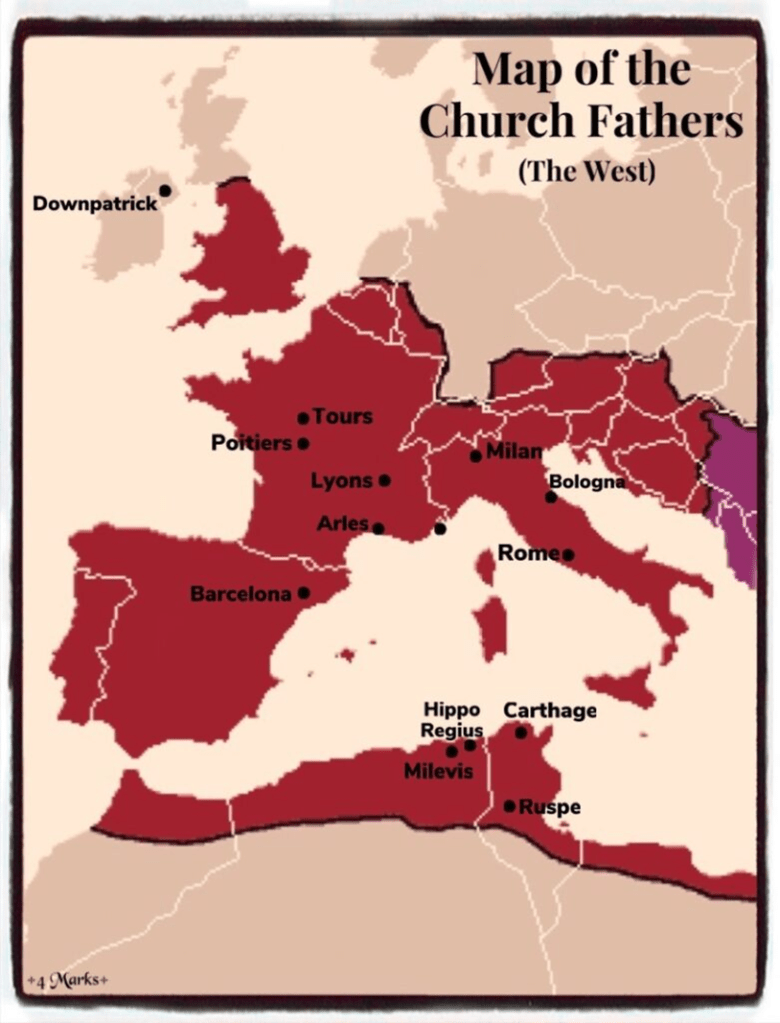

AUGUSTINE OF HIPPO – CHAPTER 5

English: The Four Doctors of the Western Church, Saint Augustine of Hippo (354–430)

Augustine of Hippo. Chapter 5. The Birth of Western Spirituality:

“Our hearts are restless until they find their rest in You, O Lord.” There really is no one quite like Saint Augustine in the history of the Church. I have always thought of him as the “template” of a kind, a type, a genre of Christian seeker. From a young age he dives head-first into living the “Big Life,” achieves all that he sets out in his heart and imagination to attain, and then finds himself a bit spent and feeling empty on the other side of having gotten all the he desired. And so God finds him on the other side of his relatively easy and prosaic victories in the secular world.

Richard H. Schmidt does a good job in his introduction of giving us a glimpse of Augustine in his life and work. And I hope that our very limited consideration of Augustine’s work and thought might tempt you to read his “Confessions,” or “The City of God.” Both are a wonderful window into the life of faith. The first, the Confessions, giving color and voice to the interior journey of faith; and “The City of God” more or less offering a theological reflection regarding the consequences of that faith within the midst of a divided, secular, world.

SAINT PATRICK AND CELTIC CHRISTIANITY

Patrick the Saint – A Short Biography

A FLEET OF 50 CURRACHS (longboats) weaved its way toward the shore, where a young Roman Brit and his family walked. His name was Patricius, the 16-year-old son of a civil magistrate and tax collector. He had heard stories of Irish raiders who captured slaves and took them “to the ends of the world,” and as he studied the longboats, he no doubt began imagining the worst.

With no Roman army to protect them (Roman legions had long since deserted Britain to protect Rome from barbarian invasions), Patricius and his town were unprepared for attack. The Irish warriors, wearing helmets and armed with spears, descended on the pebbled beach. The braying war horns struck terror into Patricius’s heart, and he started to run toward town.

The warriors quickly demolished the village, and as Patricius darted among burning houses and screaming women, he was caught. The barbarians dragged him aboard a boat bound for the east coast of Ireland.

Patricius, better known as Patrick, is remembered today as the saint who drove the snakes out of Ireland, the teacher who used the shamrock to explain the Trinity, and the namesake of annual parades in New York and Boston. What is less well-known is that Patrick was a humble missionary (this saint regularly referred to himself as “a sinner”) of enormous courage. When he evangelized Ireland, he set in motion a series of events that impacted all of Europe. It all started when he was carried off into slavery around 430.

Escape from Sin and Slavery

Patrick was sold to a cruel warrior chief, whose opponents’ heads sat atop sharp poles around his palisade in Northern Ireland. While Patrick minded his master’s pigs in the nearby hills, he lived like an animal himself, enduring long bouts of hunger and thirst. Worst of all, he was isolated from other human beings for months at a time. Early missionaries to Britain had left a legacy of Christianity that young Patrick was exposed to and took with him into captivity. He had been a nominal Christian to this point; he now turned to the Christian God of his fathers for comfort.

“I would pray constantly during the daylight hours,” he later recalled. “The love of God and the fear of him surrounded me more and more. And faith grew. And the spirit roused so that in one day I would say as many as a hundred prayers, and at night only slightly less.”

On The Mountain

Legend holds that Patrick rang a large bell (held in a reliquary, at the National Museum of Ireland) on the top of Eagle Mountain, now called Croagh Patrick. Depending on the legend, the bell scared away either Ireland’s snakes or its demons. Patrick’s other relic, a staff supposedly given to him by Jesus, was burned as an object of superstition in 1538.

After six years of slavery, Patrick received a supernatural message. “You do well to fast,” a mysterious voice said to him. “Soon you will return to your homeland.”

Before long, the voice spoke again: “Come and see, your ship is waiting for you.” So Patrick fled and ran 200 miles to a southeastern harbor. There he boarded a ship of traders, probably carrying Irish wolfhounds to the European continent.

After a three-day journey, the men landed in Gaul (modern France), where they found only devastation. Goths or Vandals had so decimated the land that no food was to be found in the once fertile area.

“What have you to say for yourself, Christian?” the ship’s captain taunted. “You boast that your God is all powerful. We’re starving to death, and we may not survive to see another soul.”

Patrick answered confidently. “Nothing is impossible to God. Turn to him and he will send us food for our journey.”

At that moment, a herd of pigs appeared, “seeming to block our path.” Though Patrick instantly became “well regarded in their eyes,” his companions offered their new-found food in sacrifice to their pagan gods.

Patrick did not partake.

The Prodigious Son Returns

Many scholars believe Patrick then spent a period training for ministry in Lerins, an island off the south of France near Cannes. But his autobiographical Confession includes a huge gap after his escape from Ireland. When it picks up again “after a few years,” he is back in Britain with his family.

It was there that Patrick received his call to evangelize Ireland—a vision like the apostle Paul’s at Troas, when a Macedonian man pleaded, “Help us!”

“I had a vision in my dreams of a man who seemed to come from Ireland,” Patrick wrote. “His name was Victoricius, and he carried countless letters, one of which he handed over to me. I read aloud where it began: ‘The Voice of the Irish.’ And as I began to read these words, I seemed to hear the voice of the same men who lived beside the forest of Foclut . . . and they cried out as with one voice, ‘We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us.’ I was deeply moved in heart and I could read no further, so I awoke.”

Despite his reputation, Patrick wasn’t really the first to bring Christianity to Ireland. Pope Celestine I sent a bishop named Palladius to the island in 431 (about the time Patrick was captured as a slave). Some scholars believe that Palladius and Patrick are one and the same individual, but most believe Palladius was unsuccessful (possibly martyred) and Patrick was sent in his place.

In any event, paganism was still dominant when Patrick arrived on the other side of the Irish Sea. “I dwell among gentiles,” he wrote, “in the midst of pagan barbarians, worshipers of idols, and of unclean things.”

Demons and Druids

Patrick did not require the native Irish to surrender their belief in supernatural beings. They were only to regard these beings in a new light as demons. The fear of the old deities was transformed into hatred of demons. If Christianity had come to Ireland with only theological doctrines, the hope of immortal life, and ethical ideas—without miracles, mysteries, and rites—it could have never wooed the Celtic heart.

Predictably, Patrick faced the most opposition from the druids, who practiced magic, were skilled in secular learning (especially law and history) and advised Irish kings. Biographies of the saint are replete with stories of druids who “wished to kill holy Patrick.”

Pilgrims

On the last Sunday of each July, between 25,000 and 30,000 pilgrims pass the saint’s statue and climb to the top of Croagh Patrick, commemorating the saint’s fasting there for 40 days and nights. Carbon dating of church ruins at the 2,710-foot summit has shown it dates from Patrick’s day, supporting the legend that says Patrick climbed it.

“Daily I expect murder, fraud or captivity,” Patrick wrote, “but I fear none of these things because of the promises of heaven. I have cast myself into the hands of God almighty who rules everywhere.”

Indeed, Patrick almost delighted in taking risks for the gospel. “I must take this decision disregarding risks involved and make known the gifts of God and his everlasting consolation. Neither must we fear any such risk in faithfully preaching God’s name boldly in every place, so that even after my death, a spiritual legacy may be left for my brethren and my children.”

Still, Patrick periodically avoided such confrontations by paying protection money: “Patrick paid the price of 15 souls in gold and silver so that no evil persons should impede them as they traveled straight across the whole of Ireland,” wrote one biographer.

Patrick was as fully convinced as the Celts that the power of the druids was real, but he brought news of a stronger power. The famous Lorica (or “Patrick’s Breastplate”—see I Rise Today), a prayer of protection, may not have been written by Patrick (at least in its current form), but it expresses perfectly Patrick’s confidence in God to protect him from “every fierce merciless force that may come upon my body and soul; against incantations of false prophets, against black laws of paganism, against false laws of heresy, against deceit of idolatry, against spells of women and smiths and druids.”

According to legend, it worked. The King, Loiguire, set up a trap to kill Patrick, but as the bishop came near, all the king could see was a deer. (Thus the Breastplate has also been known as the Deer’s Cry.)

There was probably a confrontation between Patrick and the druids, but scholars wonder if it was as dramatic and magical as later stories recounted. One biographer from the late 600s, Muirchœ, described Patrick challenging druids to contests at Tara, in which each party tried to outdo the other in working wonders before the audience:

“The custom was that whoever lit a fire before the king on that night of the year [Easter vigil] would be put to death. Patrick lit the paschal fire before the king on the hill of Slane. The people saw Patrick’s fire throughout the plain, and the king ordered 27 chariots to go and seize Patrick . . . .

“Seeing that the impious heathen were about to attack him, Patrick rose and said clearly and loudly, ‘May God come up to scatter his enemies, and may those who hate him flee from his face.’ By this disaster, caused by Patrick’s curse in the king’s presence because of the king’s order, seven times seven men fell. . . . And the king, driven by fear, came and bent his knees before the holy man . . . .

“[The next day], in a display of magic, a druid invoked demons and brought about a dark fog over the land. Patrick said to the druid, ‘Cause the fog to disperse.’ But he was unable to do it. Patrick prayed and gave his blessing, and suddenly the fog cleared and the sun shone. . . . And through the prayers of Patrick the flames of fire consumed the druid.

“And the king was greatly enraged at Patrick because of the death of his druid. Patrick said to the king, ‘If you do not believe now, you will die on the spot for the wrath of God descends on your head.’

“The king summoned his council and said, ‘It is better for me to believe than to die.’ And he believed as did many others that day.”

Yet to Patrick, the greatest enemy was one he had been intimately familiar with—slavery. He was, in fact, the first Christian to speak out strongly against the practice. Scholars agree he is the genuine author of a letter excommunicating a British tyrant, Coroticus, who had carried off some of Patrick’s converts into slavery.

“Ravenous wolves have gulped down the Lord’s own flock which was flourishing in Ireland,” he wrote, “and the whole church cries out and laments for its sons and daughters.” He called Coroticus’s deed “wicked, so horrible, so unutterable,” and told him to repent and to free the converts.

It remains unknown if he was successful in freeing Coroticus’s slaves, but within his lifetime (or shortly thereafter), Patrick ended the entire Irish slave trade.

Royal Missionary

Patrick concentrated the bulk of his missionary efforts on the country’s one hundred or so tribal kings. If the king became a Christian, he reasoned, the people would too. This strategy was a success.

As kings converted, they gave their sons to Patrick in an old Irish custom for educating and “fostering” (Patrick, for his part, held up his end by distributing gifts to these kings). Eventually, the sons and daughters of the Irish were persuaded to become monks and nuns.

From kingdom to kingdom (Ireland did not yet have towns), Patrick worked much the same way. Once he converted a number of pagans, he built a church. One of his new disciples would be ordained as a deacon, priest, or bishop, and left in charge. If the chieftain had been gracious enough to grant a site for a monastery as well as a church, it was built too and functioned as a missionary station.

Before departing, Patrick gave the new converts (or their pastors) a compendium of Christian doctrine and the canons (rules).

Self Doubt

Despite his success as a missionary, Patrick was self-conscious, especially about his educational background. “I still blush and fear more than anything to have my lack of learning brought out into the open,” he wrote in his Confession. “For I am unable to explain my mind to learned people.”

Nevertheless, he gives thanks to God, “who stirred up me, a fool, from the midst of those who are considered wise and learned in the practice of the law as well as persuasive in their speech and in every other way and ahead of these others, inspired me who is so despised by the world.”

Over and over again, Patrick wrote that he was not worthy to be a bishop. He wasn’t the only one with doubts. At one point, his ecclesiastical elders in Britain sent a deputation to investigate his mission. A number of concerns were brought up, including a rash moment of (unspecified) sin from his youth.

His Confession, in fact, was written in response to this investigation. Reeling from accusations, Patrick drew strength from God: “Indeed he bore me up, though I was trampled underfoot in such a way. For although I was put down and shamed, not too much harm came to me.”

If Patrick was not confident about his own shortcomings, he held a deep sense of God’s intimate involvement in his life. “I have known God as my authority, for he knows all things even before they are done,” he wrote. “He would frequently forewarn me of many things by his divine response.”

Indeed, Patrick recorded eight dreams he regarded as personal messages from God. And scattered throughout his Confession are tributes to God’s goodness to him: “Tirelessly, I thank my God, who kept me faithful on the day I was tried, so that today I might offer to him, the Lord Jesus Christ, the sacrifice of my soul. He saved me in all dangers and perils . . . . So, whatever may come my way, good or bad, I equally tackle it, always giving thanks to God.”

According to the Irish annals, Patrick died in 493, when he would have been in his seventies. But we do not know for sure when, where, or how he died. Monasteries at Armagh, Downpatrick, and Saul have all claimed his remains. His feast day is recorded as early as March 17, 797, with the annotation; “The flame of a splendid sun, the apostle of virginal Erin [Ireland], may Patrick with many thousands be the shelter of our wickedness.”

Ultimate Model

It is difficult to separate fact from fiction in the stories of Patrick’s biographers. It is historically clear, however, that Patrick was one of the first great missionaries who brought the gospel beyond the boundaries of Roman civilization. According to tradition, he had established bishops throughout northern, central, and eastern Ireland. Only Munster, in the south, was to remain pagan until a century after Patrick’s death.

Patrick was the ultimate model for Celtic Christians. He engaged in continuous prayer. He was enraptured by God and loved sacred Scripture. He also had a rich poetic imagination with the openness to hear God in dreams and visions and a love of nature and the created.

He is, then, most worthy of the appellation saint, as one “set apart” for a divine mission. As such, he became an inspiring example. Hundreds of Celtic monks, in emulation of Patrick, left their homeland to spread the gospel to Scotland, England, and continental Europe.

It is a legacy Patrick was proud of: “For God gave me such grace, that many people through me were reborn to God and afterward confirmed and brought to perfection. And so then a clergy was ordained for them everywhere.”

More resources:

The best starting place to learn about Patrick is with his own words. Few doubt his authorship of the autobiographical Confession and his angry Letter to Coroticus, available in several books, including a new translation by John O’donohue.

The works are also available in Saint Patrick’s World by Liam de Paor. Combining primary source documents with an informative 50-page “introduction,” it should be in the library of anyone interested in this topic.

If you’re interested in more detail, check out the biography In the Steps of St. Patrick by Brian De Breffny.

By Mary Cagney

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #60 in 1998]

Mary Cagney, a former editorial resident at Christianity Today, has written a screenplay titled A Celtic King. The author of this piece, Mary Cagney, is a former editorial resident for the news department of Christianity Today, where she wrote several articles on the North Ireland peace process.

St. Patrick

“We rush through our days in such stress and intensity, as if we were here to stay and the serious project of the world depended on us. We worry and grow anxious; we magnify trivia until they become important enough to control our lives. Yet all the time, we have forgotten that we are but temporary sojourners on the surface of a strange planet spinning slowly in the infinite night of the cosmos.”

― John O’Donohue, Eternal Echoes: Celtic Reflections on Our Yearning to Belong

“Prayer shaped their consciousness, so that they became ever more aware that the Kingdom of Heaven is a constant and present reality, hidden within the veil of everyday life.”

― Ray Simpson, Celtic Prayers for the Rhythm of Each Day

Good Afternoon Friends,

We meet next Thursday, September 25th, in the Cathedral Library to continue our reading with Chapter 5, 6, and possibly 7. This will include St. Augustine, St. Patrick, and Benedict of Nursia. I do hope that you will take care to read Richard Schmidt’s introductions to each writer. Historical context matters in these readings, as these were individuals giving articulation to spiritual truths they received in the midst of living daily life. We will begin our conversation by addressing the questions at the end of each chapter – you may want to read with that in mind.

If you find yourself stymied by a particular quote or question, spend a moment on it, and then simply move on. There is so much spiritual “meat” in this book that you find your way like following breadcrumbs through a forest. Take what is useful and truthful, and then leave the rest for later.

I have updated the page on my blog, and will be doing so throughout, if you would like some thoughts and additional conversation on the chapters we are reading together.

You can find it here: https://thecarpentersnail.blog/god-seekers-book-group-group-notes/

You will notice that “GOD SEEKERS BOOK GROUP – GROUP NOTES” is at the top of my blog as a link.

Our next session will be September 25th, 5:30, in the Cathedral Library. Please feel free to come and go as works best for you.

Blessings and Godspeed,

Alston

BENEDICT OF NURSIA – WESTERN MONASTACISM

How Benedict’s Rule can guide your spiritual practice

Benedictine wisdom helps us become monks in the world.

Christine Valters Paintner, Published August 8, 2019

St. Benedict is a wise guide and presence in my life through the teachings he left in his Rule for monasteries. Benedict was born in Nursia, Italy and died at the abbey he founded in Monte Cassino (c. 480–547). All that we know of his life comes from Pope Gregory the Great, who wrote a biography about the monk and saint 50 years after Benedict’s death. Gregory describes how Benedict lived for three years in a cave in Subiaco as a hermit until others began to seek him out and formed a community around him. There are miracles associated with the saint as well. He is said to have performed several, including bringing a child back to life.

The Hildegard connection

I have been a Benedictine oblate for 15 years. To be a Benedictine oblate means to commit oneself as a layperson to live out the Rule of St. Benedict in the everyday world. Although Benedict wrote his Rule 1,500 years ago, what is perhaps most remarkable is how well its wisdom endures. Today it continues to guide the spiritual practice of thousands of communities around the world.

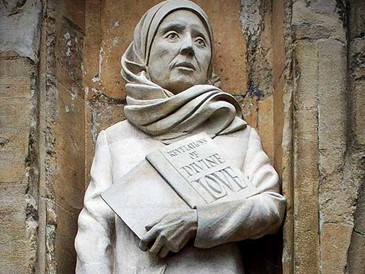

I first discovered the Benedictine way when I was in graduate school. In studying for my history of Christian spirituality exam I encountered St. Hildegard of Bingen, a 12th-century Benedictine abbess from Germany who was a preacher, theologian, visionary, musician, artist, herbalist, and spiritual director. The more I studied her, the more I wanted to learn about this Benedictine tradition in which she was so steeped.

I consider Hildegard to be the patron saint of my becoming an oblate. She opened the door for me into this contemplative way of life that so resonated with who I was and how I longed to pray. In Benedict’s Rule I discovered a beautifully balanced vision for the spiritual life, both in solitude and in community. Benedict did not believe in harsh, ascetic practices. He was critical of those who aimed for a kind of spiritual competition or went to extremes of fasting or other forms of self-denial.

Benedictine spirituality and disability

Two books by author and theologian Mary Earle for those living with chronic illness helped me fall even more in love with the Rule’s commitment to balance, moderation, and finding a healing rhythm to life: Beginning Again: Benedictine Wisdom for Living with Illness (Morehouse Publishing) and Broken Body, Healing Spirit: Lectio Divina and Living with Illness (Morehouse Publishing). I struggled with rheumatoid arthritis for much of my 20s. I still have the disease, but it is mostly controlled with medication. The Benedictine path helped me to claim the contemplative way, which I saw was not only truer to my nature but also more nourishing of a life lived with physical limitations.

In studying Benedict’s Rule I also discovered the practice of lectio divina, which means “sacred reading.” This practice is one of the oldest Christian contemplative ways of prayer. Traditionally used to pray with scripture and other sacred texts, lectio divina has inspired me to see all of life as a sacred text in which to listen for a holy word from icons, music, and nature.

There are three primary commitments in the Benedictine way that form the spiritual backbone for the rest of the spiritual practices—obedience, stability, and conversion.

Obedience, stability, and conversion

The root of the word obedience means “to hear” and is about making a commitment to listen for God’s voice in the world and respond when you hear the call. Obedience is a difficult concept for modern Western thinkers. Consider it as a way of deep listening for the holy in all dimensions of your life. The second part of this listening is a response: Am I willing to not only make the time and space to listen for God’s call, but to also respond with my full self?

Stability for monastics means making a commitment to a particular monastery for a lifetime. For those of us who are committed to monastic practices outside of the monastery walls, consider it as a commitment to be present to life circumstances even through challenges. This might apply to a marriage or friendship, to our work life, or simply to daily challenges. Can I stay present to the moment and how God is speaking even when I’m uncomfortable or in conflict? Or do I want to run in the other direction?

Then there is conversion, which for me essentially means making a commitment to always be surprised by God. Conversion is the counterpart to stability. It is the recognition that we are all on a journey and always changing. God is always offering us something new within us. How might my spiritual life transform by opening myself up to the new possibilities God is continually offering each moment?

Sacred hospitality

One of my favorite lines from Benedict’s Rule is: “All guests who present themselves are to be welcomed as Christ, for he himself will say: I was a stranger and you welcomed me.” I love this invitation to welcome that which feels the most strange and uncomfortable as the very face of the divine. The stranger might be outside of us but just as easily is within us. We each have parts of ourselves we try to push away. In the Benedictine monastic tradition, everything is considered sacred—all people, all things, and all of time. The stranger at the door is to be welcomed in as Christ. The kitchen utensils are to be treated just like the altar vessels. The hours of the day call us to remember the presence of God again and again so that time becomes a cascade of prayers.

In 2009 I traveled to Rome for the World Congress of Benedictine Oblates, where I met other oblates from around the world. We made pilgrimages to sacred sites connected with Benedict, such as the cave in Subiaco and Monte Cassino, the central monastery he founded high upon a hill. Monte Cassino is a large and flourishing place where many pilgrims seeking spiritual connection go. I still treasure my Benedict medal from there, which I wear daily around my neck as a symbol of my commitment.

Benedictine wisdom forms the heart of my daily spiritual practice, along with the teaching I do. I call it becoming a monk in the world, to learn how to embrace this way of being and offer it as a gift to a world always so busy and frenzied. In living this way I witness to an alternative way of being, one rooted in slowness and spaciousness, one inspired by what Benedict called the “inexpressible delight of love.”

This article also appears in the August 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 8, pages 45–46).

CHAPTER 8 – SYMEON THE NEW THEOLOGIAN – EXPERIENCING THE SPIRIT

Anglican Spirituality Group – October 30th – 5.30 – Cathedral Library

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

“If you know that all visible things are a shadow and all pass away, are you not ashamed of playing with shadows and hoarding transitory things? Like a child you draw water with a bucket full of holes; do you not realize it and take it into account, my dear friend? As though there were nothing more serious than appearance and illusion, as though reality has been taken from them?”

+ St. Symeon the New Theologian

Good Evening Friends,

I hope that you are doing well on this rainy night. Our next session will begin with a continuance of Chapter 7 – “Western Monasticism – Benedict of Nursia.” Benedict has always been a favorite of mine and Liza’s, and I could probably “go on” a bit about the Western Monastic tradition. There is much for us to gather from that tradition as we are each negotiating our journey through modernity. If you listen closely to psychological suggestions and advice for modern peace of mind, you will find that much of it has deep roots in the mixture of the contemplative and active life that is balanced in monasticism.

We will also visit about the life and thought of Symeon The New Theologian who comes to us from the Eastern and Orthodox world of medieval Christianity. I find him fascinating and compelling, with a grasp of what lies beyond “The Beyond.” In my own studies, I have always found that theologians and Christian thinkers sometimes have the greatest difficulty describing or offering quantification for the Holy Spirit. I am reminded of an old philosophical trope that was asked by Ludwig Wittgenstein who said, ““Describe the smell of coffee without using the word “coffee.”” It poses a nearly impossible challenge; I find descriptions of the Holy Spirit are similar. The only real explanation lay in the experience of the Holy Spirit itself.

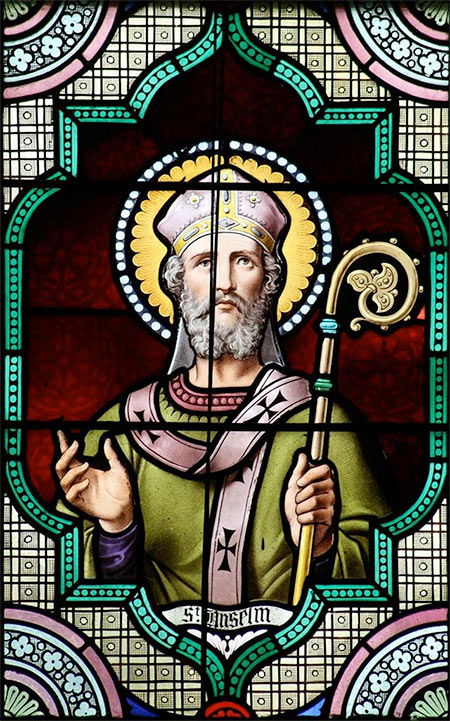

And of course if we have time we will move onto Anselm of Canterbury – one the greats of our own Anglican tradtion.

You can notes and videos here:https://thecarpentersnail.blog/god-seekers-book-group-group-notes/

You will notice that “GOD SEEKERS BOOK GROUP – GROUP NOTES” is at the top of my blog as a link.

Our next session will be October 30th, 5:30, in the Cathedral Library. Please feel free to come and go as works best for you.

Blessings and Godspeed,

Alston

Symeon The New Theologian, Bishop Kallistos Ware, The Study of Spirituality, ed. Cheslyn, Wainwright, Yarnold

(Oxford University Press, 1986) pp. 235-242.

| § 1. Introduction: Byzantine Theology |

‘He became man that we might be made god’; he became ‘incarnate’ that we might be ‘ingodded’. So St Athanasius of Alexandria sums up the message of salvation in Christ (De Incarnatione, 54). The EasternOrthodox tradition has sought to give full emphasis to both parts of his statement. ‘He became man’: the implications of this were explored more especially by the Greek Fathers from the fourth to the seventh centuries. What does it mean to affirm that Jesus Christ is fully God, truly human, and yet a single undivided person? It was in response to this three-sided question that the first six Ecumenical Councils, from Nicaea I (325) to Constantinople III (680), developed the classic expression of Trinitarian theology and Christology. In the centuries that followed, the main focus of attention shifted from the first to the second part of Athanasius’ dictum: ‘. . . that we might be made god’. What are the effects of the divine incarnation in the life of the Christian? What is signified by the fulness of ‘ingodding’ or ‘deification’ (theōsis)? How is it possible for the human person, without ceasing to be authentically human, to enjoy direct and transforming union with God in his glory? These are the master themes of later Byzantine theology and spirituality.

Two writers in this period stand out with particular prominence: in the eleventh century, St Symeon the New Theologian, and in the fourteenth, St Gregory Palamas. Each is rooted in the past, but both are at the same time explorers, developing the earlier tradition in fresh ways.

From the ninth century onwards Greek Christianity tended to be strongly conservative, and all too often its spokesmen remained content with a barren ‘theology of repetition’. Typical of this outlook is the somewhat discouraging comment of the Byzantine scholar Theodore Metochites (d. 1332), ‘The great men of the past have expressed everything so perfectly that they have left nothing more for us to say’ (Miscellanea, preface: cited in S. Runciman, The Last Byzantine Renaissance. CUP, 1970, p. 94). There was in the Greek East nothing equivalent to the startling rediscovery of Aristotle and the dynamic evolution of scholasticism in the West during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries; in the East the patristic period of theology continued uninterrupted until 1453, and indeed beyond. But, throughout the twelve hundred years of Byzantium, alongside continuity there is also change; and the finest representatives of later Byzantine thought, such as Symeon and Palamas, succeed in combining loyalty to the past with creative originality. Later Byzantine spirituality is marked above all by three features:

1. A strong insistence upon the divine mystery and so upon the apophatic approach to God; he is utterly transcendent, beyond all concepts and images, beyond all human understanding.

2. A balancing sense of the nearness as well as the otherness of the Eternal; not only transcendent but immanent, God can be known here and now, in this present life, through direct personal experience.

3. A preference for the symbolism of light rather than darkness; mystical union with God takes above all the form of a vision of divine radiance, the dominant ‘model’ being Christ transfigured upon Mount Tabor.

| § 2. Biography of Symeon |

St Symeon the New Theologian (949-1022) exemplifies all three of these features, but more particularly the second. In a manner altogether exceptional in the Christian East — for there is in Greek patristic literature no autobiographical work equivalent to the Confessions of St Augustine -Symeon refers explicitly to his own personal experiences. Enthusiastic, unsystematic, he is a ‘theologian’, not in the modern academic sense, but rather according to the older understanding of the term: a man of prayer, of personal vision, who speaks about the divine realm, not in a theoretical fashion, but on the basis of what he has himself seen and tasted. The designation ‘new’ in his title, according to the most persuasive interpretation, implies a comparison first of all with St John the Evangelist or the Divine (in Greek, theologos, ‘the Theologian’), and then with St Gregory of Nazianzus, ‘ Gregory the Theologian’ as he is known in the Christian East. The name ‘New Theologian’ means, then, that St Symeon in the eleventh century renewed the tradition of mystical prayer to which St John bore witness in the first century and St Gregory of Nazianzus in the fourth.

Destined originally for a political career, at the age of fourteen Symeon the New Theologian passed under the influence of a monk at the monastery of Studios in Constantinople, also named Symeon, known as Eulabes, ‘the devout’. Profoundly marked by the example of his own spiritual father, in his teaching the younger Symeon stresses the vital need for living, personal direction in the spiritual life. He would have agreed with the Hasidic master Rabbi Jacob Yitzhak that ‘the way cannot be learned out of a book, or from hearsay, but can only be communicated from person to person’ (M. Buber, [ET] The Tales of the Hasidim [ New York, Shocken Books, 1947], vol. i, p. 286). The importance of the spiritual father is, indeed, a recurrent theme throughout later Byzantine spirituality: ‘Above all else’, say Kallistos and Ignatios Xanthopoulos (fourteenth century), ‘search diligently for an unerring guide and teacher’ (On the Life of Stillness, § 14).

When Symeon was aged about twenty and still a layman, he received the first in a series of visions of divine light. Seven years later he became a monk. For a quarter of a century he was abbot of the monastery of St Mamas in Constantinople; his last thirteen years were passed outside the city, in a small hermitage on the opposite shore of the Bosphorus. Thus the central and most creative period of his life was spent, not in seclusion, but as superior of a busy community in the heart of the imperial capital; he is an ‘urban Hesychast’, a mystical theologian who combines inner prayer with pastoral and administrative work. In his understanding of monastic life he blends the cenobitic approach of St Basil the Great and St Theodore the Studite with the more solitary, eremitic spirit of St John Climacus. During his life and after his death he aroused sharp controversy — in particular, because of the cult that he rendered to his spiritual father as a saint, without waiting for official approval, and because of his views on priesthood and confession — but the Byzantine Church ended by canonizing him.

| § 3. Awareness of Divine Indwelling |

Symeon displays an especially close affinity with the Spiritual Homilies attributed to Macarius. Whatever the truth about the supposed Messalian character of the Homilies (cf. p. 160), there is no good reason to attribute to the New Theologian the kind of Messalianism that might be suspected of heresy. What Symeon shares with the Homilies is above all an emphasis upon conscious, personal awareness of Christ and the Spirit. Christianity, so he is passionately convinced, involves much more than a formal, dogmatic orthodoxy, than an outward observance of moral rules. No one can be a Christian at second hand; the tradition has to be relived by each one of us without exception, and each should feel the indwelling presence of the Holy Spirit in a conscious, palpable manner:

| Do not say, It is impossible to receive the Holy Spirit;Do not say, It is possible to be saved without him.Do not say, then, that one can possess him without knowing it.Do not say, God does not appear to men,Do not say, Men do not see the divine light,Or else, It is impossible in these present times.This is a thing never impossible, my friends,But on the contrary altogether possible for those who so wish(Hymn XXVII, 125-32). | μὴ λέγετε ἀδύνατον λαβεῖν τὸ θεῖον πνεῦμα·μὴ λέγετε χωρὶς αὐτοῦ δυνατὸν τὸ σωθῆναι· (125)μὴ οὖν ἀγνώστως τούτου λέγετέ τινα μετέχεινμὴ λέγετε, ὅτι θεὸς οὐχ ὁρᾶται ἀνθρώποις·μὴ λέγετε, οἱ ἄνθρωποι φῶς θεῖον οὐχ ὁρῶσιν,ἢ ὅτι καὶ ἀδύνατον ἐν τοῖς παροῦσι χρόνοις·οὐδέποτε ἀδύνατον τοῦτο τυγχάνει, φίλοι, (130)ἀλλὰ καὶ λίαν δυνατὸν τοῖς θέλουσιν ὑπάρχει· |

If in this passage and elsewhere Symeon comes close to identifying the reality of grace with the conscious feeling of grace, as the Messalians were accused of doing, he does sometimes allow for a real yet hidden activity of the Spirit on an unconscious level (see, for example, Chapters, III, 76). The aim, however, is always to advance beyond this unconscious grace to the point of explicit awareness, at which we experience the Spirit ‘in a conscious and perceptible way’, with what he calls the ‘sensation of the heart’. In the passage quoted above, it is significant that Symeon vehemently repudiates any suggestion that the charismata granted to holy men and women in the past are no longer accessible to Christians in the present time. For him this was the worst of all heresies, implying as it does that the Spirit has somehow been withdrawn from the Church. We are in exactly the same situation as the first Christians, he protests; if grace is not as apparent among us today as it was once among them, the sole reason is the weakness of our faith.

| § 4. The Power to Absolve Sins |

Symeon applies this teaching about direct experience more especially to confession and absolution. Who, he asks in his letter On Confession, is entitled to ‘bind and loose’? The answer is surprising. There is one essential qualification, and one only, which enables a person to act as confessor and spiritual father, and that is a conscious awareness of the Holy Spirit:

Do not try to be a mediator on behalf of others until you have yourself been filled with the Holy Spirit, until you have come to know and to win the friendship of the King of all with conscious awareness in your soul (Letter i, 10: Holl, p. 119).

From this Symeon draws a double conclusion: negatively, that anyone who lacks this conscious awareness — even though he may be bishop or patriarch — should not, and indeed cannot, exercise the ministry of confession; positively, that lay monks who possess such awareness, even though not in holy orders, may be called to exercise this ministry.

Most Orthodox would hesitate to go the whole way here with Symeon. It is true that in the Christian East, from the fourth century up to the present, there have been many instances of lay monks acting as spiritual fathers. Symeon’s own ‘elder’, Symeon the Studite, was not a priest -although the New Theologian himself was — and many of the leading spiritual fathers on the Holy Mountain of Athos today are likewise lay monks; within Orthodoxy the ministry of eldership is at times exercised equally by nuns who act as spiritual mothers. But is this ministry of eldership or spiritual direction identical with the sacrament of confession, strictly defined? Although Symeon makes no distinction between the two, many other Orthodox would wish to do so. One point, however, emerges unambiguously from Symeon’s answer about confession: the high significance that he attaches to direct personal experience of God.

| § 5. Vision of the Divine Light |

This direct experience takes the form, in Symeon’s teaching, more especially of the vision of divine light. Here Symeon, speaking of himself in the third person, describes the first such vision that he received:

| WHILE he was standing one day and saying the prayer God be merciful to me a sinner (Luke 18:13), more with his intellect than with his mouth, a divine radiance suddenly appeared in abundance from above and filled the whole room. | ¨Ισταμένου οὖν αὐτοῦ ἐν μιᾷ καὶ τὸ « ̈̔Ο Θεός, ἱλάσθητί μοι τῷ ἁμαρτωλῷ» λαλοῦντος τῷ νοῒ μᾶλλον ἢ τῷ στόματι, ἔλλαμψις θεία πλουσίως αἴφνης ἐπέφανεν ἄνωθεν (90) καὶ πάντα τὸν τόπον ἐπλήρωσε. |

| When this happened, the young man lost all awareness of his surroundings and forgot whether he was in a house or under a roof. He saw nothing but light on every side, and did not even know if he was standing on the ground […] | Τούτου δὲ γεγονότος ἠγνόησεν ὁ νεανίας καὶ ἐπελάθετο εἰ ἐν οἴκῳ ἦν ἢ ὅτι ὑπὸ στέγην ὑπῆρχε. Φῶς γὰρ μόνον ἔβλεπε πάντοθεν καὶ οὐδὲ εἰ ἐπὶ γῆς ἐπάτει ἐγίνωσκεν. |

| He was wholly united to non material light and, so it seemed, he had himself been turned into light. Oblivious of all the world, he was overwhelmed with tears and with inexpressible joy and exultation | (95) […] ἀλλ’ ὅλως φωτὶ ἀΰλῳ συνὼν καὶ τῷ δοκεῖν αὐτὸς φῶς γενόμενος καὶ παντὸς τοῦ κόσμου ἐπιλαθόμενος, δακρύων καὶ χαρᾶς ἀνεκφράστου καὶ ἀγαλλιάσεως ἔμπλεως ἐγένετο. |.. (100) |

| Greek Text: B. Krivochéine and J. Paramelle, Syméon le Nouveau Théologien, Catéchèses [Sources Chrétiennes 96, Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1963] |

(Catechesis XXII, lines 88-100).

Note how Symeon’s experience combines sorrow with joy. Before the vision he prays for mercy, and when the vision comes he sheds tears; yet they are tears not of penitence only but of rejoicing. The light that enfolds him is evidently far more than a metaphorical ‘light of the understanding’. It is an existent reality, and yet at the same time it is not a physical and created light, but spiritual and divine; as he affirms throughout his writings, the light is God himself. This divine light has upon Symeon a transforming effect; he is taken up into that which he contemplates, and is himself ‘turned into light’. Yet, though transfigured, he does not lose his personal identity, but is never so truly himself as when within the light. If the account of Symeon’s first vision might seem to suggest that the light is impersonal, elsewhere he insists upon the personal presence of Jesus within the divine radiance: the Lord speaks to him from the light, and the vision involves a dialogue of love between them. Symeon’s light mysticism is not just ‘photocentric’ but Christocentric.

Although Symeon almost always describes the mystical union in terms of light, not of darkness, he is at the same time an apophatic theologian, frequently applying negative language to God; the first of the three features mentioned above is present as well as the second and the third. ‘You are higher than all essence,’ he says to the Creator, ‘than the very nature of nature, higher than all ages, than all light . . . You are none of the things that are, but above them all’ (Hymn XV, 67-71). Yet, while ‘invisible, unapproachable, beyond our understanding and our grasp’ (XV, 75), God has at the same time become truly human and is known by the saints in a vision face to face. To express this double truth that God is at once transcendent and immanent, unknown yet well known, the fourteenth-century Hesychasts make use of the distinction between the divine essence and the divine energies: although beyond all understanding in his essence, God reveals himself and enters into personal communion with us through his energies. Sometimes Symeon likewise employs this distinction (e.g. Hymn XXIV, 11; XXXI, 6-7), but elsewhere he ignores it, stating that humans can partake even in the very essence of God (e.g. Hymn VII, 25-29). His usage is not consistent, and it would be misleading here to read back into his thought the more developed position of the later period. In general, however, he exercised an important influence on the fourteenth-century Hesychasts.

| § 6. Sacramental Theology and the Body |

Three other points call for mention:

First, an absence: there is no reference in Symeon’s authentic writings to the Jesus Prayer. Here again a difference should be noted between Symeon and the later Hesychasts.

Secondly, Symeon’s vision of the spiritual way, as well as being Christocentric, is also deeply sacramental. In particular, he refers to the Eucharist in strongly realistic terms: [But the metrical prayer commencing From polluted lips. . ., used by Orthodox before communion and commonly attributed to Symeon the New Theologian, is almost certainly not his work but that of his contemporary St Symeon Metaphrastes (‘the Translator’)].

| My blood has been mingled with your Blood,And I know that I have been united also to your Godhead.I have become your most pure Body, | καὶ μιγὲν τὸ αἷμά μου τῷ αἵματί σουἡνώθην, οἶδα, καὶ τῇ θεότητί σουκαὶ γέγονα σὸν καθαρώτατον σῶμα, (15) |

| A member dazzling, a member truly sanctified,A member glorious, transparent, luminous …What was I once, what have I now become!… | μέλος ἐκλάμπον, μέλος ἅγιον ὄντως,μέλος τηλαυγὲς καὶ διαυγὲς καὶ λάμπον […]ἐκ ποίου οἷος ἐγενόμην […] |

| Where shall I sit, what shall I touch,Where shall I rest these limbs that have become your own,In what works or actions shall I employThese members that are terrible and divine? (Hymn II, 13-29). | (25)τὸ ποῦ καθίσω καὶ τίνι προσεγγίσωκαὶ ποῦ τὰ μέλη τὰ σὰ προσανακλίνω,εἰς ποῖα ἔργα, εἰς ποίας ταῦτα πράξειςὅλως χρήσομαι τὰ φρικτά τε καὶ θεῖα· |

Thirdly, Symeon displays a profound reverence for the body, which he sees in Hebraic, biblical terms as an integral part of the human person — to be sanctified, not hated and repressed. This was something that he had learnt from his spiritual father Symeon the Studite, of whom he says:

| He was not ashamed of the limbs of anyone,Or to see others naked and to be seen naked himself.For he possessed the whole Christ and was himself wholly Christ;And always he regarded all his own limbs and the limbs of everyone else,Individually and together, as being Christ himself . (Hymn XV, 207-11) | οὗτος οὐκ ἐπῃσχύνετο μέλη παντὸς ἀνθρώπουοὐδὲ γυμνοὺς τινὰς ὁρᾶν οὐδὲ γυμνὸς ὁρᾶσθαι·εἶχε γὰρ ὅλον τὸν Χριστόν· ὅλος αὐτὸς Χριστὸς ἦν, (210)καὶ μέλη ἅπαντα αὐτοῦ καὶ παντὸς ἄλλου μέληκαθ’ ἓν καὶ πάντα ὡς Χριστὸν οὗτος ἀεὶ ἑώρα |

Here, as in the account of his first vision of the divine light and in his words of thanksgiving after Holy Communion, we see how for Symeon the total person, body and soul together, is hallowed and permeated by grace and glory. A monk and an ascetic, he yet has no sympathy for the platonizing or Gnostic outlook that depreciates the body, excluding it from the process of salvation. In Symeon’s eyes ascetic self-denial is a battle not against but for the body.

| § 7. Conclusion: Hymnody and Poetry |

Vivid, full of personal warmth, St Symeon the New Theologian is an unusually attractive writer. His spirituality is perhaps expressed most eloquently in the fifty-six Hymns of Divine Love written towards the end of his life, from which we have quoted more than once. A theologian poet, in the long line extending from St Ephrem the Syrian, through Dante, St John of the Cross, Milton and Blake, up to T. S. Eliot and Edwin Muir in our own century, he exemplifies the close link existing between theology and poetry. Often it is the poets who are the best theologians of all. It would be good for the Church if we paid them greater heed.

TEXTS AND TRANSLATIONS

There is a critical Greek text, with French tr., in SC (9 vols. so far; one to follow); the main writings exist also in ET.

i. Chapters [Theological, Gnostic and Practical Chapters], ed. J. Darrouzès and L. Neyrand, SC 51 (2nd edn, 1980); ET P. McGuckin, Cistercian Studies Series 41 (Kalamazoo, 1982).

ii. Catecheses or Discourses, ed. B. Krivochéine and J. Paramelle, SC 96, 104, 113 (1963-5); ET C. J. de Catanzaro, CWS XXI.

iii. Theological Treatises, ed. J. Darrouzès, SC 122 (1966); ET McGuckin (see i above).

iv. Ethical Treatises, ed. J. Durrouzès, SC 122, 129 (1966-7).

v. Hymns, ed. J. Koder and J. Paramelle, SC 156, 174, 196 (1969-73); also ed. A. Kambylis (Berlin, 1976); ET G. A. Maloney (Denville, N.J., Dimension Books, no date).

vi. Letters: to appear in SC. For Letter 1 (On Confession), see K. Holl, Enthusiasmus und Bussgewalt beim griechischen Mönchtum: Eine Studie zu Symeon dem neuen Theologen (Leipzig, Hinrichs, 1898), pp. 110-27 (Greek text only).

vii. Life of St Symeon by Nicetas Stethatos: Greek text and French tr. I. Hausherr and G. Horn, Orientalia Christiana 12 (45) (Rome, 1928).

STUDIES

Krivochéine B., Dans la lumière du Christ. Saint Syméon le Nouveau Théologien 949-1022, Vie — Spiritualité — Doctrine. Chevtogne, 1980.

Maloney G. A., The Mystic of Fire and Light: St. Symeon the New Theologian. Denville, N.J., Dimension Books, 1975.

Völker W., Praxis und Theoria bei Symeon dem neuen Theologen. Wiesbaden, Steiner, 1974.

Jung and the spiritual path: