He made known to us the mystery of his will according to his good pleasure, which he purposed in Christ, to be put into effect when the times reach their fulfilment—to bring unity to all things in heaven and on earth under Christ. – Ephesians 1:9-10

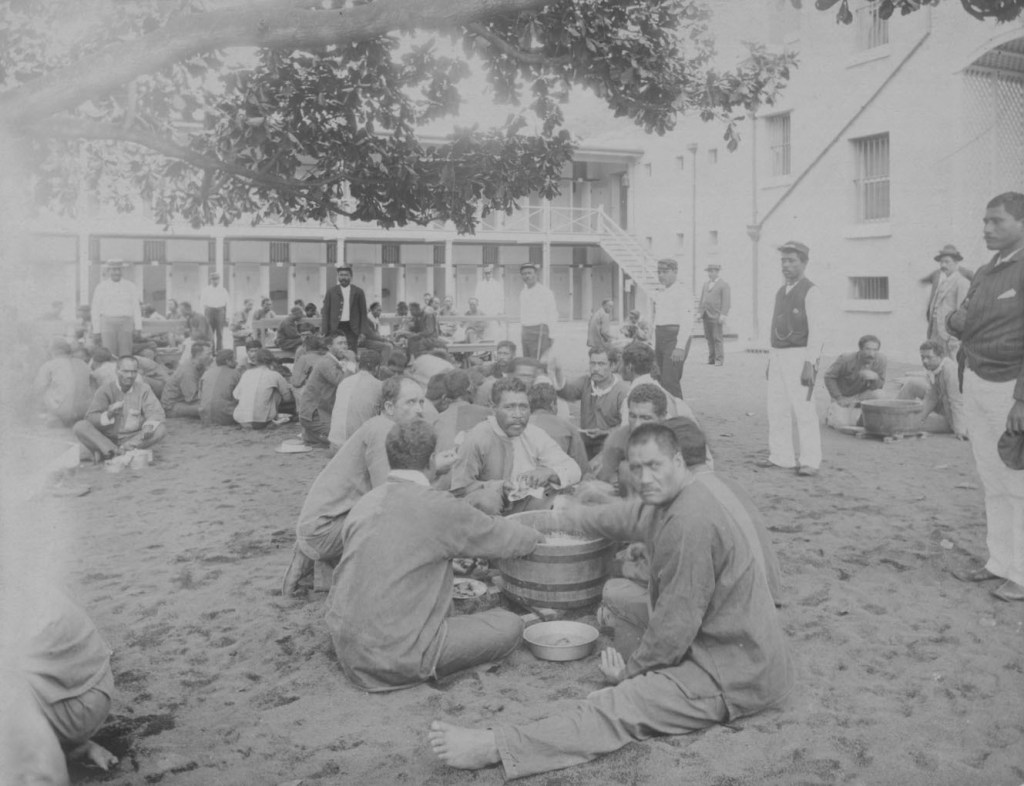

Imagine Paul in prison in Ephesus. He is probably malnourished and short of sleep. He may well have suffered horrible illness; he will certainly have been beaten up by guards and perhaps by other prisoners. He feels helpless and alone in the dark and damp, with the smell of rot, excrement, and death all around him. Picture him then, either scribbling away on a small sheet of papyrus, squinting for lack of light, or else, hearing at last someone whispering through a slot in the door, talking to a visiting colleague and telling him what to put in a letter to one or more of the central Asian churches.

This is a far darker image than the usual portraits of Paul, sitting peacefully at a desk, quill in hand, with a pensive look on his face like Wordsworth writing about daffodils. What Paul experienced in an Ephesian prison was not serenity, but searing hardship, not soothing tranquillity but brokenness and anxiety. So it is all the more remarkable that it is from this tumultuous period of Paul’s career that we get from him, not only the letter to the Philippians, but also the letters to Philemon, the Colossians, and the circular letter we call ‘Ephesians’. The church in Colossae, inland from Ephesus, seems to have been founded only recently, with Philemon as one of its local leaders, and a particular problem has caused Paul to write to Philemon as an individual while sending a letter of encouragement, rich with the sense of the Messiah’s supremacy over all things, to the new believers there. Ephesians may then have been written shortly afterwards, to be sent to all the churches in the region. These letters all emphasize the universal sovereignty of Jesus and the call for the churches to model, in their own communities, the cosmic reconciliation achieved by God through him.

Paul’s Ephesian ministry and the origins of the Lycus valley churches

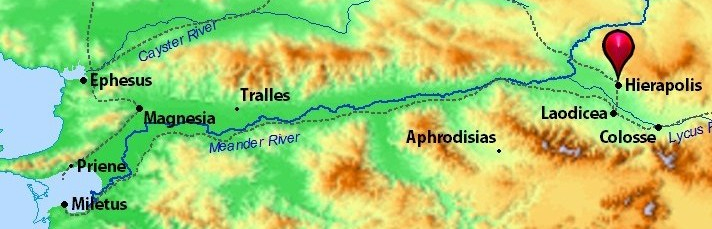

Paul was the first to bring the gospel to Ephesus, though the city later became a hub for other Christian groups, including those associated with the apostle John. Paul’s first visit there was brief, lasting only a few weeks. Paul did, however, return to Ephesus, perhaps during the summer of AD 52, and stayed there for the better part of three years. Luke provides brief snapshots from that period: Paul’s ministry to some followers of John the Baptist, his initial preaching in a Jewish synagogue, and (after being forced to leave) his daily discussions in the lecture hall of Tyrannus. During this period Paul’s co-workers seem to have established churches in the Asian cities of Pergamum, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Thyatira, and in the western interior of Asia Minor in the Lycus valley, in the towns of Laodicea, Hierapolis, and Colossae. It looks as if, during this time, Paul met Philemon and his wife Apphia, gentiles from Colossae, and led them to faith; Philemon was thereafter a ‘partner’ with Paul, probably meaning that he contributed financially to Paul’s work. A native of the Lycus valley named Epaphras evangelized the cities of Colossae, Laodicea, and Hierapolis, until he joined Paul in Ephesus; he may also have been imprisoned with Paul at the time of these letters. In Epaphras’s absence the Colossian church may have been led by Archippus, though meeting in Philemon’s house, while the church in Laodicea was led by Nympha and met in her house.

Paul’s powerful ministry in Ephesus had three immediate results: a split in the synagogue community, leading to continuing opposition; the burning of magical scrolls by many who, in a strong local tradition, had practised various kinds of sorcery; a decline in the worship of the goddess Artemis.

During this period, then, Paul probably ended up in an Ephesian prison at least once, facing the prospect of a capital trial and perhaps even death. He later praises Priscilla and Aquila who ‘risked their necks’ for him during this period, and he mentions Aristarchus in one letter, and Epaphras in another, as ‘fellow-prisoners’. This evidence points to a complex time with many twists and turns now mostly hidden from us.

It is possible to connect some dots and do some guesswork on how the three Asian letters were composed. First, while in prison, Paul received Onesimus, a slave who had either run away or absconded from Philemon, but who was now contrite and had come to faith in the lord Jesus. Paul wrote to urge Philemon to receive Onesimus back as a fellow-believer, hinting that Philemon might then release Onesimus so he could work with Paul. Second, Paul wanted to warn the churches in the Lycus valley to be on their guard against the varied challenges that might come from the Jewish community, and sent (via Onesimus and Tychicus22) a letter which put this warning in a larger, and pastorally encouraging, context. The letter we call ‘Ephesians’ was probably a circular, a general exhortation to all the Asian churches, based largely on Colossians but broader in content and scope. Some suggest it may have been drafted by Paul’s co-workers while Paul himself was incapacitated. This might well be the ‘letter from Laodicea’ that Paul mentions in Colossians. During this time it is possible that Paul suggested to John Mark that he should make a pastoral visit up the Lycus valley.

After his release, Paul left Ephesus sometime in AD 54/5. We assume from what he says in the letter to Philemon that he will have gone to Colossae, but after that his aim was to get to Corinth, for reasons we shall study later. Rather than sail straight across the Aegean, he decided to go north to Macedonia, and then on to southern Greece to gather up his projected ‘collection’ before heading to Jerusalem.

EPHESUS

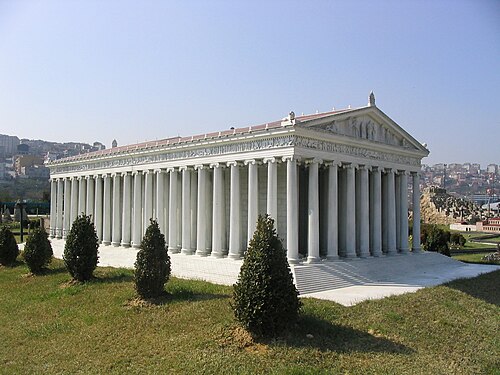

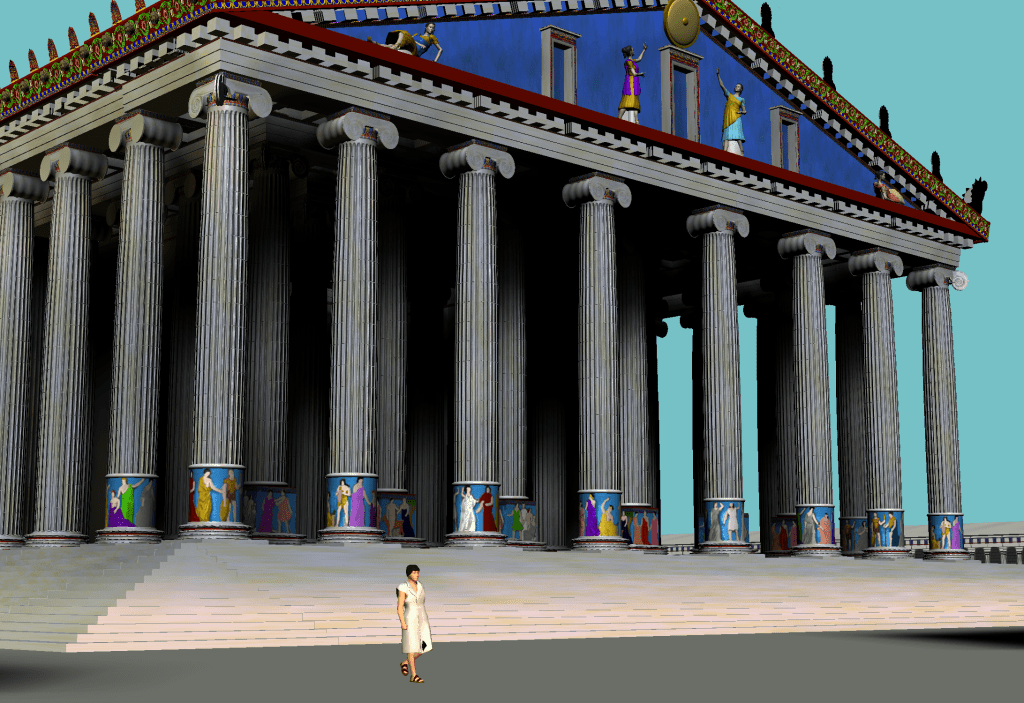

Ephesus was lauded by ancient authors as ‘the first and greatest metropolis of Asia’, the ‘light of Asia’, and the ‘market of Asia’. Strategically located on the sea and land routes, it had vast commercial, cultural, and military importance. The city contained a magnificent amphitheatre, aqueducts, a gymnasium, a stadium, two agoras, impressive gates, and a basilica. In Paul’s day it had a population of around 200,000. Only Rome and Alexandria exceeded Ephesus in size and grandeur. Jews were probably a significant minority of the city, but they had a history of mixed relations with the city’s officials and Greek populace.

In terms of religious sites, Ephesus had temples to Zeus and Apollos, to the goddess Roma, and to the emperor Augustus. But larger than all, and four times larger than the Athenian Parthenon, the famous temple to Artemis (Roman ‘Diana’) was situated on the north-eastern edge of the city, one of the wonders of the ancient world, an icon of Ephesus in the same way that London is known by Big Ben and Sydney by its Opera House. Artemis was acclaimed as ‘Queen of Heaven’ and venerated by adherents as ‘Lady’ and ‘Saviour’. She was associated with protection from evil spirits, illness, and misfortune. The Artemision was a place of banking, sacrifice, and asylum. Twice a week a procession of devotees took place through the city. The image of the goddess adorned local coins, a month of the year was named after her, games were held in her honour, and she was revered as the divine guardian and benefactor of the city. A measure of the importance of Artemis and her shrine was that a sanctuary dedicated to the emperor Augustus was located within its precincts.

Colossae and the Lycus valley

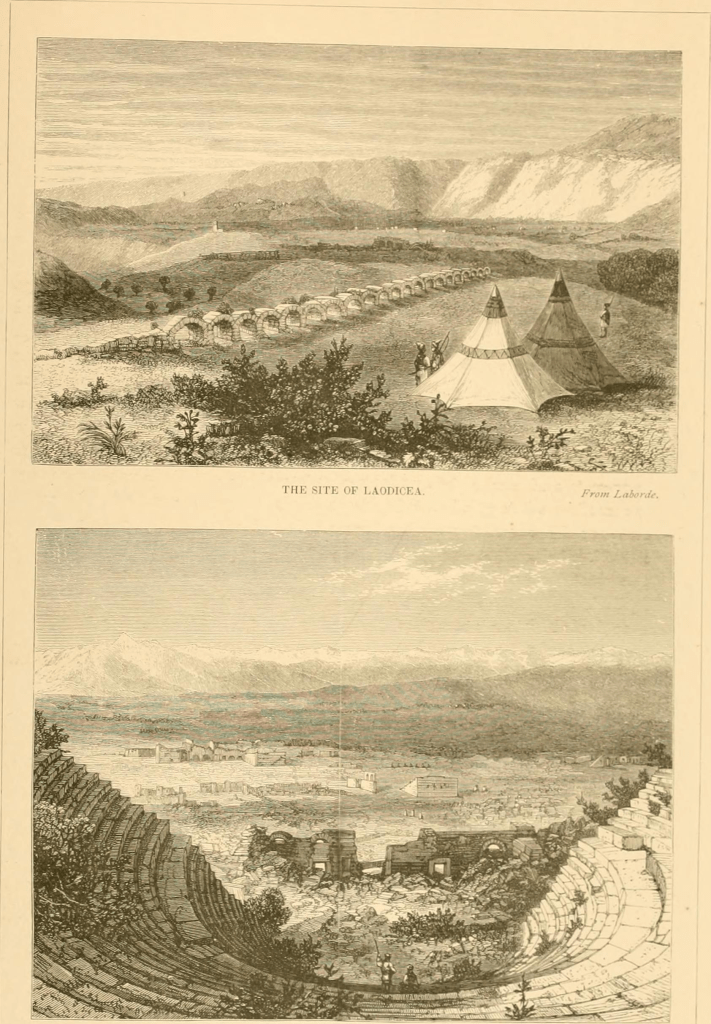

Colossae, one of the older cities in the Lycus valley (going back to at least the fifth century BC), was set within south-western Phrygia in the western interior of Asia Minor. Colossae was then, however, dwarfed by the larger cities of Hierapolis and Laodicea, founded during the Seleucid era, each with a population of around 10,000. The three cities are within a day’s walk of each other. Colossae, with the surrounding region, was devastated by an earthquake in the early or middle 60s, and, though some civic life may have been reassembled, the city never really recovered. Eventually, at some point during the Byzantine era, the populace abandoned the area, probably moving to the neighbouring town of Chonai. Colossae has never been excavated. Only meagre remains of a necropolis, fragments of columns and architraves, some coins and pottery, and a handful of inscriptions have so far been uncovered. We have to rely on more general information about the Lycus valley to gain a picture of Colossae in the first century.

In 133 BC the last king of Pergamum bequeathed his kingdom to the Romans, who later reorganized it as ‘the province of Asia’. The cities of the Lycus valley were then incorporated into the Roman empire. Eventually the network of Roman roads reached the Lycus valley, turning the area into a significant hub in east–west travel. The cults of Zeus and Apollo were prominent in the region; evidence from coins shows the continuance of older Phrygian religions such as the cult of Men Karou.

There had been a significant Jewish population in the Lycus valley since the time of the Seleucid empire in the third and second centuries BC. During the Roman period, Laodicea became a collection-point for the payment of the Temple-tax by local Jews; in 62 BC the proconsul of Asia, Lucius Valerius Flaccus, attempted to seize the collection which, according to Cicero, consisted of twenty pounds of gold. In addition, numerous Jewish sarcophagi have been discovered in Hierapolis, indicating a sizeable Jewish presence in the Lycus valley. This resonates with Philo’s statement that the Jews dwelt in every city of Asia Minor. Colossae, we rightly assume, was no different.

Authorship of Colossians and Ephesians

Most have accepted that Paul really did write the letter to Philemon. But in the last 150 years or so Ephesians and Colossians have regularly been regarded as non-Pauline or deutero-Pauline. That conclusion was partly based on comparisons of style and language with the undisputed letters, but emerged largely, we suspect, because they do not support the liberal protestant paradigm for reading Paul which dominated the scholarly world for several generations. Quite simply, Ephesians in particular, and Colossians to a considerable extent, seem to have a much stronger and higher view of the church—and, indeed, of Jesus himself—than many scholars have been prepared to allow.

The real Paul, such scholars assumed, taught ‘justification by faith’, and since this was held to be radically incompatible with what was seen as a high view of the church, Paul could not have written letters that offered one. Sadly, despite the fashion of new ‘political’ and ‘sociological’ readings of Paul, no-one seems to have noticed that the more rounded view of Paul that has emerged from such studies creates a context into which Ephesians and Colossians fit extremely well, with Paul’s vision of Christ as sovereign over ‘the powers’, and his interest in forming and shaping the early communities rather than merely saving souls. One might suppose that passages like Ephesians 6.12 and Colossians 1.12–14; 2.14–15 would get a green light from ‘political’ readers of Paul, offering as they do a high christology set over against the powers of the evil age.

Or, again, one might suppose that Ephesians 2.11–21 and Colossians 3.11, encouraging ethnic unity in the churches, would be recognized as embodying central Pauline themes which emerge equally powerfully in Galatians and Romans. This has not happened. Instead, we still hear the scholarly mantra that Ephesians and Colossians are on the ‘dubious’ list, sometimes being cited, astonishingly, as advocating social conformism, with diminished apocalyptic enthusiasm and egalitarian ethos, settling down into a comfortable bourgeois existence of theological bureaucracy and ecclesiastical hierarchy. This position, ironically, reflects a modern social conformism—to the ‘unwritten rules’ of the scholarly guild, and to the modern political liberalism that underlies them.

In fact, if it’s stylistic differences we want, one might suggest that the most striking are those between 1 and 2 Corinthians. The second letter to Corinth is much jerkier than the first; its sentences are dense and convoluted, bending back on themselves, twisting to and fro with language about God, Jesus Christ, and Paul’s ministry. The organization of material is much less crisp.

There is a far greater difference between those two Corinthian letters than there is between Galatians and Romans on the one hand and Ephesians and Colossians on the other; yet nobody uses that as an argument against the authenticity of 2 Corinthians.

As John A. T. Robinson pointed out from his personal experience a generation ago, a busy church-leader may well write in very different styles for different occasions and audiences. The same person can be working simultaneously on a large academic project, with careful, ponderous sentences, and a short, snappy talk for the Sunday school. More directly to the point, it has recently been argued that Ephesians and Colossians show evidence of an ornamented, almost pompous, ‘Asiatic’ rhetorical style, which Paul, after many months in the region, could easily have adopted.

One speculative suggestion might be that Paul penned the letter to Philemon himself, that he collaborated with Timothy on the letter to the Colossians, and that the circular we call ‘Ephesians’ was written under Paul’s supervision by his co-workers, based largely on Colossians. But it is just as possible that Paul, one of the most energetic and flexible writers of his day or any day, wrote them all himself.

A Colossian heresy?

The authors of the present book are divided. MFB suggests that the philosophy seems quite specific, and that the use of the indefinite pronouns indicates a group or individual (Col. 2.8, 16, 18). NTW follows Morna Hooker in suggesting that there actually were no ‘false teachers’ in Colossae, and that Paul merely writes a general admonition to urge the members of the congregation there not to conform to the beliefs and practices of their Jewish and pagan neighbours.

If we suppose that Paul was indeed attacking something he refers to as a ‘philosophy’ (2.8), we might see it in terms of an amalgamation of Jewish thought and practice on the one hand (given the references to the sabbath [Col. 2.16], circumcision [Col. 2.11], and food laws [Col. 2.21]) and pagan ideas on the other (with the references to the ‘powers’ [Col 1.16; 2.8, 10, 15], the ‘worship of angels’ [Col. 2.18], asceticism [Col. 2.21–23], festivals [Col. 2.16], and wisdom [Col. 1.9; 2.3, 23; 3.16]).

The Lycus valley does seem to have been a melting-pot of various religions, philosophies, and systems of magic, facilitating all kinds of syncretism. Attention has focused particularly, though, on proposals to do with types of Jewish mysticism, perhaps dressed in a garb of hellenistic philosophy and language, appealing to ex-pagan gentile believers. However, once the argument has gone that far, and once we look closely at the ways in which Paul warns against the blandishments of Jewish teaching elsewhere (e.g. Phil. 3.2), it is straightforward to apply Occam’s Razor (the principle of not multiplying unnecessary hypotheses) and conclude that it was Paul himself who was dressing Jewish themes in pagan garb, precisely in order to warn against them, as in Galatians or Philippians.

The central thrust of Colossians 2, after all, is the affirmation that followers of Jesus are the true monotheists (2.9), that they have already been circumcised (2.11–12), that the Torah can no longer exclude them (2.14–15), and that they ought not to adopt the Jewish food laws (2.10–23). The other details fit well around this. The warnings of 2.8, 16–19 and elsewhere can then be seen as contemptuous references to those who might try, for reasons we would call ‘cultural’ and ‘political’ as much as ‘religious’ or ‘theological’, to inveigle the new believers into joining the synagogue community. The debate will no doubt continue.

THE ARGUMENT OF COLOSSIANS

- Greetings, thanksgiving, and prayer (1.1–14)

Paul thanks God for the news, from Epaphras, that a community of love has sprung up in Colossae. Clearly the gospel message is bearing fruit among the believers there (1.3–8). This moves him to pray for an increase in knowledge, wisdom, and the corresponding behaviour (1.9–12). When he speaks of God rescuing people from one kingdom and giving them another one (1.13–14), of ‘redemption’ and ‘forgiveness’, he is speaking of the ‘new exodus’ accomplished in the Messiah. - The Messiah poem and the gospel (1.15–23)

Colossians 1.15–20 is one of the most remarkable early Christian writings, articulating in the way that only poetry can the symmetry of, and the coherent movement between, creation and new creation, both accomplished in, through, and for the Messiah. Many suppose that Paul is quoting a hymn written by someone else, and that is always possible, though it is equally possible that he wrote it himself, perhaps as a result of his own dark night of the soul. This poem, celebrating the absolute lordship of Jesus over all other authorities, human or otherwise (see ‘Emails from the edge: firstborn’), is the foundation of the rest of the letter, not just for verses 21–23 which apply the message to the Colossians in particular. In sum: ‘The pre-existent lord of the world has become the human lord of the world, and in so doing has reflected fully, for the eyes of the world to see, the God whose human image he has now come to bear.’ And, extraordinarily, Paul declares that this gospel has already been announced to the whole creation (1.23). This can only mean that with Jesus’ death and resurrection the old world has been judged and the new world has been born—and that all creation somehow knows it.

‘According to the author of Colossians, the house of Nympha offered the perfect space for the performance of this text (4:15–16). Colossians 4:16 calls for a public reading of Paul’s letter in the church of Laodicea that in all likelihood met in Nympha’s house. Here it is the modern interpreter who encounters irony. We are to imagine patriarchal teaching calling for the subjugation of wives to husbands proclaimed in a spaced ruled by a woman. Nympha’s status as a widowed (?), well-to-do woman may have rendered her largely exempt from the impact of the restrictions. Her house and status in the wider community may have offered the church a semblance of protection and respectability – suitable sanctuary for an ethos that relativized the rubrics of household and citizenship within the confines of an invisible spiritual body. We cannot hear her own voice, but in the world of emerging Christianity Nympha herself may have viewed such ethical teaching as obvious and prudent. Or, like many women throughout history who have been confronted with hierarchical authority structures, she may have known that she could work around the rules.’

Margaret MacDonald, ‘Can Nympha Rule This House?: The Rhetoric of Domesticity in Colossians,’ 115.

- Messianic woes, messianic mission, and messianic mystery (1.24—2.5)

Paul then announces that he is celebrating his own suffering on behalf of the Colossians, probably reflecting the Jewish belief that salvation would come through a time of intense suffering. He has been working hard for them and longs to see them firmly established (2.1–5). - Engaging the empty deceit of Jewish mysticism (2.6–23)

Paul’s basic exhortation consists of the reminder that those who belong to Jesus the Messiah are already complete: he is all they need. They should, therefore, watch out for anyone who tries to divert them; particularly for anyone who tries to get them to join the synagogue community as a kind of surety for belonging to God. Jesus and his victory on the cross is sufficient (2.14–15) to save them and include them in God’s family. (See ‘Portals and parallels: Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice’.) They should, therefore, watch out for anyone who tries to divert them; particularly for anyone who tries to get them to join the synagogue community. If they are concerned about living the new moral life, the answer is not to take up Jewish practices but to recognize and capitalize on what is true of them ‘in the Messiah’: they have already died and been raised and must put that into practice (2.20–23; 3.1–4). - Christians as transformed and renewed (3.1–17)

The ‘heavenly’ life does not mean having one’s head in the clouds (3.1–4). It means killing off the vices of sex and speech (3.5–8). For God’s new humanity, the old distinctions of race, tribe, gender, and social status do not exist. Nothing lies outside the sphere of the - Messiah’s sovereign rule (3.5–11). What matters, then, is the life of compassion and love, and the forgiveness which reflects, and the gratitude which responds to, God’s own generous love (3.12–17).

- Christian homes in pagan cities (3.18—4.1)

Paul offers brief guidelines for family life. These early Christian household codes (here and in Ephesians and 1 Peter) are about the ways in which the lordship of Jesus will be manifest in the most obvious social unit. Pagan critics were poised to accuse the Christians of threatening the social order; Paul’s resistance to this has nothing to do with ‘patriarchy’ as normally conceived and everything to do with mutual, humble love. - Prayer request, further instructions, and benediction (4.2–18)

The epistle rounds off with final exhortations, a commendation of the ministry of Paul and his co-workers, final greetings, and a blessing.

THE ARGUMENT OF THE LETTER TO PHILEMON

Paul’s letter to Philemon has some interesting similarities to that of Pliny to Sabinianus. The most obvious is the standard rhetorical ploy: ‘Far be it from me to force your hand—I wouldn’t tell you what to do, now, would I?’ No, no, of course not, think Sabinianus and Philemon with a wry smile; you merely put me in an impossible position! Friendship, at various levels, is a standard theme right across the world of ancient letter-writing (see ‘Portals and parallels: Pliny’s letter to Sabinianus’).

There is, however, a shocking dissimilarity. Pliny writes as a social superior; Paul writes as a prisoner, which he mentions not as though it decreases his social standing but as though it gives him a higher status. Once we study the two letters side by side, we see that they breathe a different air. There is, after all, a world of difference between saying, ‘Now, my good fellow, let me tell you what to do with your stupid freedman and then we’ll all be safely back in our proper social positions,’ and saying, ‘Now, my brother and partner, let me tell you about my newborn child, and let me ask you to think of him, and yourself, and me, as partners and brothers.’ Paul is articulating something different: a new way of life, with new patterns of thinking to sustain it.

This letter is basically a challenge to Philemon to think carefully and messianically about how the koinōnia (‘fellowship’) between the lord Jesus, Paul, and himself is to be applied to Onesimus (see box: ‘Outline of Philemon’). When Philemon comes to a full practical knowledge of the meaning of this fellowship, that knowledge will work powerfully towards full unity in Christ and result in transformed relationships within the community. Paul’s concern for the runaway slave Onesimus reflects his larger concern for messianic unity across traditional boundaries in the churches, whether it be the unity of Jew and gentile in the Messiah (the main point of Galatians), the unity of the church under the lordship of the Messiah in a pagan and imperial context (part of the point of Philippians), or, as here in Philemon, the unity of master and slave, expressing again what it means to be en Christō. ‘So,’ Paul asks, ‘if you reckon me a partner [koinōnos], welcome him [proslabou auton] as you would welcome me.’ That is the main thrust of the letter.

Paul’s threefold appeal unfolds in verses 8–22. First, accept Onesimus back; do not punish him, but receive him as if he were me, a reconciled brother in Christ (though still as a slave). Second, please send him back to me as an assistant. Third, perhaps implied, in doing so, you will also give him his freedom. If we are right, Paul is teaching Philemon, and indeed Onesimus, to think within the biblical narrative, to see themselves as actors within the ongoing scriptural drama: to allow their erstwhile pagan thought-forms to be transformed by a biblically based renewal of the mind. Here we see one of the most fundamental differences between Pliny and Paul. Pliny’s appeal, we remind ourselves, reaffirmed the social dynamics already present. Paul’s appeal openly subverted them (see box: ‘Paul and slavery’).

We should add that if a young man called Onesimus were indeed to return to Ephesus to work alongside Paul in the mid-50s, it is not entirely impossible that he is the same person referred to sixty years later by Ignatius of Antioch as the bishop of Ephesus in around AD 110. This, however, must remain uncertain, not least since the name was common. If it is the same Onesimus, however, it shows that Paul’s vision had taken root in Ephesus, and that the church was indeed a place of reconciliation, fellowship, and mutuality where ecclesial offices were determined by love, devotion, and spiritual and intellectual gifts, not social status or grouping.

THE ARGUMENT OF EPHESIANS

Letter opening, acclamation of praise, and thanksgiving (1.1–23)

1.The earliest manuscripts lack the words ‘in Ephesus’. We have argued above that ‘Ephesians’ was originally a circular letter intended for churches in western Asia Minor, acquiring its name through being part of a collection of letters perhaps based in Ephesus.

After the opening greeting, Paul pours out a majestic hymn of praise, woven through with the exodus-shaped story of what God has done in Jesus the Messiah. God’s purpose was ‘to bring unity to all things in heaven and on earth under Christ’ (1.10), and believers are now folded into that plan. Paul therefore prays that they would understand more fully who they really are ‘in the Messiah’, and the power with which they are thereby invested.

- Salvation by grace through faith (2.1–10)

Paul then reminds his Asian readers of their own prior personal history of enmity with God. They were dead in their sinfulness, imprisoned by the trinity of evil (world, flesh, and devil), and courting divine wrath (2.1–3). But God’s loving mercy has found them and rescued them ‘by grace through faith’, placing them within his larger healing and restorative purposes for the world, as living examples of God’s artistry (2.4–10). - The unity of Jews and gentiles in the renewed Israel (2.11—3.13)

The result is that Jews and gentiles now come together in the Messiah: God has broken down the dividing wall between them (Paul may be thinking of the barrier in the Temple keeping non-Jews out of the inner courts). Instead, God has established a new Temple where he now dwells by the spirit: the single multi-ethnic messianic family. The united church is not an optional extra to the work of redemption, but is itself part of the reality of gospel, the way in which God is taking forward his plan for the whole cosmos to radiate with his glory (2.11–22). Paul’s own role has been to be the specific agent through whom this new work comes about (3.1–13), confronting the powers of the world with the new ecclesial reality (3.10).

- Paul’s prayer for the Ephesians (3.14–21)

Paul therefore prays for the young churches, that they may discover the heart of what it means to be followers of Jesus. It means knowing God as the all-loving, all-powerful father, putting down roots into that love; or, changing the picture, having that love as the rock-solid foundation for every aspect of one’s life. - Paul’s exhortation to unity and maturity (4.1–16)

Ephesians 4—6 emphasizes Paul’s great hope for the church: unity and holiness. The multiple ministries given by the spirit are given to build up the one body, enabling it to withstand distractions and temptations (4.7–16). - Put off the old and put on the new (4.17—5.20)

The united church must learn holiness by discovering what it means to have put off the old human nature and put on the new. Old pagan ways are dehumanizing and to be shunned. Renewal must start in the mind and issue in a new style of life (4.17–24). Work, speech, and communal living will all change (4.25–32). Sacrificial love, modelled in the gospel, must be the believers’ rule of life (5.1–2). Once they were darkness; now they are light (5.8–10). - Christian houses in a pagan city (5.21—6.9)

As in Colossians, only somewhat more fully, Paul now provides instructions on the relationships within Christian households. Mutual submission is the order of the day, a somewhat different ethical basis from today’s flattened and puzzling egalitarianism. His idea of male headship is modelled on the Messiah’s self-giving love. Giving instructions to children and slaves, thereby treating them as responsible human beings, was itself revolutionary (6.1–9).

- Withstanding opposition from the powers (6.10–20)

A church that even begins to appropriate all that has been said so far will face satanic opposition, as Paul knew well from experience. The believers must therefore learn to use the spiritual weapons the gospel provides. Paul himself needs prayer in his own continuing ministry. - Letter closing and benediction (6.21–24)

Tychicus will deliver not only this circular letter but also updated news of Paul, intending to encourage all the churches. There follows a final benediction.

COLOSSIANS, PHILEMON, AND EPHESIANS, AND THE BIG PICTURE

Reading Acts 19 alongside 2 Corinthians 1 reveals the triumphs and travails that Paul encountered in the Roman province of Asia in the early 50s. Opposition came from many quarters, not only local Jewish groups but also the social and cultural forces that rallied around the cults of Artemis, Zeus, and the Roman empire. Paul’s answer given in Colossians is to think more deeply about the victory and supremacy of Jesus over all other powers, the fulfilment of Israel’s scriptures in him, and the vocation of the church to unity and holiness as the sign to the world of the new way of being human. All creation is under Jesus’ lordship, and the church must model what that means. That comes into sharp focus in the letter to Philemon, where Paul is revealed, not as an abstract theologian removed from the mess of human relationships, but as a wise and warm-hearted pastor and friend, coming to the aid of the vulnerable, standing in the breach where necessary, and suffering reproach without thought. Paul instructs Philemon out of partnership, not power, and urges him to think through in the Messiah what he ought to do and how the principle of the gospel (there is neither slave nor free, and so on) applies to himself and Onesimus. This short letter shows how to do pastoral persuasion in the light of the new creation.

Ephesians sums much of this up, as indeed it may have been intended to do. Paul’s clear and celebratory statement of the grace of God in the gospel is anchored in his vision of God’s cosmic plan to unite heaven and earth in the Messiah—a plan symbolized by the coming together of Jew and gentile in the church and also of husband and wife in marriage. The powers of darkness will resist this, and Christians will therefore find themselves on the front line of spiritual warfare.

All quotes in this post are taken from “The New Testament in Its World An Introduction to the History, Literature, and Theology of the First Christians” N. T. Wright (Author) , Michael F. Bird (Author)